How bad are term-time holidays really?

Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Education myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

Once my son starts school, I do not plan to whip him out for a term-time mini-break, partly because official holidays already seem long, and partly because I am determined to carry my old title of “teacher’s pet” into adulthood. But then again, Marilyn Monroe once quipped: “If I’d observed all the rules, I’d never have got anywhere.” What does the evidence say?

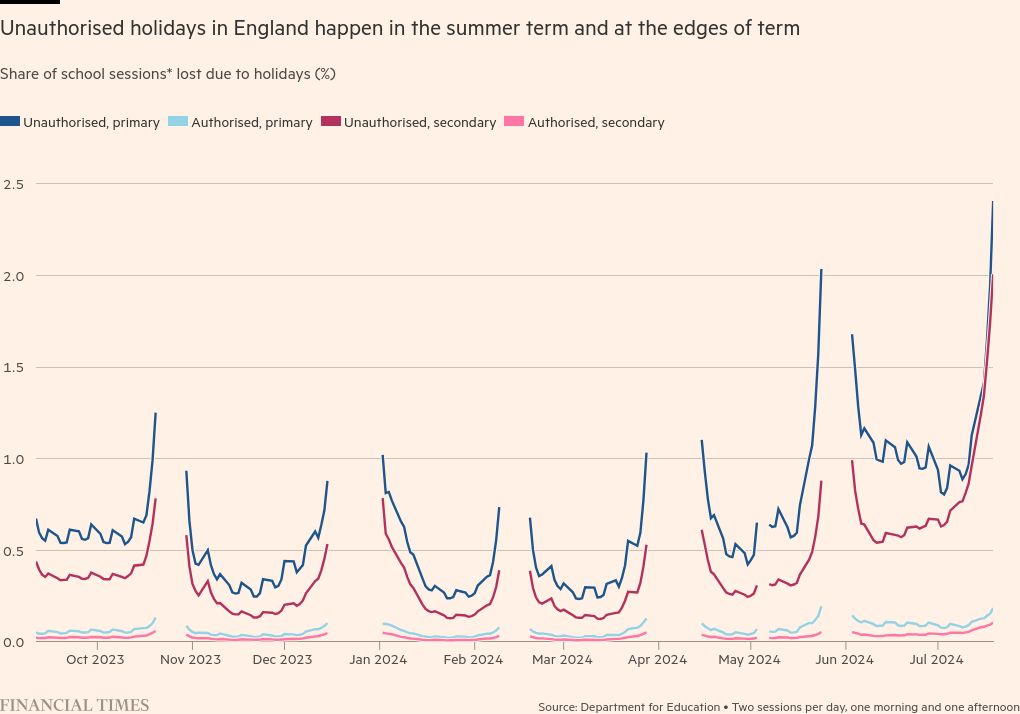

A growing number of parents, particularly those of primary school-aged children, appear to be taking inspiration from Monroe. This is less important than the broader disengagement from school since the pandemic, but not trivial. In England last academic year holidays accounted for about two-fifths of unauthorised absences in primary schools, and an eighth of those in secondary schools. A new study suggests the true share could be even higher. It finds a “Friday effect” on unexplained absences, especially before half-terms and bank holidays.

Information on exactly who is swapping books for the beach is thin, but my anecdata includes wealthy jet-setters, those visiting extended families overseas and bargain-hunters. A quick online search, for example, reveals a 50 per cent discount for shifting a package holiday two weeks before the upcoming October half-term.

The government has been hurling schemes at the general problem of absenteeism, including mandatory attendance reporting for schools. It just raised fines for missing more than five full days of school from £60 to £80, and has pushed local authorities to apply them more consistently. (Holiday-makers account for nine in 10 such fines.)

There is also finger-wagging on the government’s education hub, which includes a section titled: “What are the risks of missing a day of school?” It explains that whereas around five in six pupils with perfect attendance achieved the expected standard at key stage 2, only two in five of persistently absent pupils did.

For a parent dreaming of some cheap September sun, this sort of comparison might not convince. Is persistent absence really comparable to families snatching a few horizon-broadening experiences at the edges of term? And what if problems at home are contributing to both poor attendance and weak academic performance?

Economists have tried various ways of pinning down the causal effects of absences. One study of Swedes born in the 1930s by Sarah Cattan of Nesta and co-authors compares siblings missing different amounts of school to try to strip out the effects of their family circumstances. It finds that missing 10 days of primary school curbs earnings in 1970 by as much as 2 per cent though advances in teaching could well mean that today there is more scope for children to catch up.

Then there is a working paper by Joshua Goodman of Boston University, which studies pupils living in Massachusetts in the 2000s. He isolates the effect of absences on achievement by comparing years with more or less snow, and finds significant effects on maths scores. Those are somewhat bigger in schools where poverty is more prevalent, supporting the idea that students’ ability to catch up depends on their resources at home.

Another study of Californians in the 2000s and early 2010s exploits the fact that the effect of a given absence on learning time will depend on the student’s timetable. It finds effects on both English and maths scores, that absences in the spring term (closer to exams) are worse, and that while all absences are harmful, the cost of one extra day away as part of a longer absence is smaller than the effect of a single day in isolation. But surprisingly, they don’t find evidence that catch-up is worse in poorer schools than in richer ones.

None of these studies would pick up the broader effects of absences. When a child comes back from holiday having missed some lessons, catching them up sucks up teachers’ time, which might otherwise be spent helping needier classmates. The effects of each incident are probably imperceptibly small, but over time they add up.

What should policymakers do to instil the belief that getting somewhere can mean staying put? Perhaps higher fines will do something. Ian Mansfield of Policy Exchange and a former UK government adviser says that schools should play their part in showing parents that every day really does count. (This will raise eyebrows among the teachers who told me that they were already trying hard.) The trade association for British travel agents has suggested that staggering school holidays would even out demand. To which I say, good luck with that.

Follow Soumaya Keynes with myFT and on X

The Economics Show with Soumaya Keynes is a new podcast from the FT bringing listeners a deeper understanding of the most complex global economic issues in easy-to-digest weekly episodes. Listen to new episodes every Monday on Apple, Spotify, Pocket Casts or wherever you get your podcasts

#bad #termtime #holidays