How to measure liquidity

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Good morning. War in the Middle East has, quite rightly, pushed markets and finance off the FT’s homepage and most-read rankings. But the world of money keeps on turning. Email and tell us what is going on while the world’s attention is elsewhere: [email protected] and [email protected].

Your regular liquidity update

Unhedged looks at liquidity conditions every couple of months, because we are convinced — at least in the abstract — by what we can loosely call the liquidity theory of markets: that when there is an increasing amount of cash around, investors try to get rid of the stuff, an attempt that pushes asset prices up. Similarly when the cash tide rolls out, asset prices will tend to fall. This stands in contrast to the fundamental theory of markets, where asset prices fluctuate around a stable mean set by the present value of their future cash flows.

The problem is that liquidity is not at all easy to track. The amount of cash in the system is hard to quantify, and showing how and when it affects prices is tricky.

With that somewhat uneasy introduction, let’s have a look at current conditions. Back in June, we looked at the popular federal liquidity proxy, which consists of:

-

The Fed’s balance sheet, or the Treasuries and agency securities it has bought out of the market, replacing them with cash

-

Plus the bank term funding program, a Fed cash facility for banks

-

Minus the Fed’s reverse repo balances, which the Fed uses to control it’s policy rate by pulling cash out of the system overnight

-

Minus the Treasury’s general account, which represents taxes collected but not yet distributed — that is, cash pulled out of the system

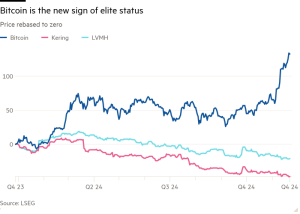

Charts of the proxy alongside the S&P 500 were very popular in 2021 and 2022, when the two moved together. But they have stopped doing so, and the divergence has only grown since we wrote in June. Federal liquidity is falling outright and the market continue to rise:

The pure theory of federal liquidity, aka “printer go Brr,” (or is it “Brrr”? We need a style ruling on this) is looking worse all the time.

Several readers have argued that the liquidity proxy ought to include something else: Treasuries and agency securities held on bank balance sheets. The idea is that while government bond issuance has no net effect on liquidity (government has more cash; private sector has less), when the bond is owned by a bank, it is matched by a deposit on the liability side of the bank’s balance sheet — and the amount of money in the financial system is increased. For example: the government writes me a stimulus cheque for $1,000. I deposit the money in a bank, and the bank uses the deposit to buy a Treasury. There are now more deposits (money) in the system. If I’d just received the check and bought the Treasury directly, there would be no impact on liquidity.

The level of government bonds on bank balance sheets has been rising this year, from about $4tn to about $4.4tn. But adding this to the Federal liquidity proxy is not enough to make it correlate — even roughly — with the sharp rise in the stock market over the past year:

Perhaps we need a different, and preferably wider, measure of liquidity. Readers have urged me to simply look at US bank reserves held at the Fed as a measure of extra cash sloshing around the system. But those have been drifting down this year too, in the opposite direction as the market:

So let’s go simpler still, and just look at the money supply. Here is M2:

At least M2 is rising. But only very gently. Can that really explain the strength of this rally?

Given the refusal of the US big-cap stock index — the biggest, deepest reservoir of risk assets in the world — to line up neatly with all these measures of liquidity, can the liquidity theory of asset prices be salvaged? Here are some options:

-

We could argue that liquidity operates on assets with (to use a neat phrase I just came up with myself) long and variable lags. What matters, in other words, is the huge increase in the total level of liquidity from 2020 to 2022 (and even in the years following the great financial crisis), rather than the changes in liquidity over shorter periods. That massive level continues to echo through markets in an uneven way. I find this idea quite appealing, though it has a downside. It deprives the liquidity theory of its predictive power. It says “there was a huge burst of money, and that will keep asset prices high for some unknown period of time.” Probably true, not very useful.

-

We could argue that prices are anticipating an increase in liquidity that will be driven by Fed rate cuts. As rates fall, that should all else equal increase credit creation (indeed total bank credit has been rising gently since early this year). And credit creation is money creation. We’ll have to see if this plays out; if there is a recession, it won’t.

-

We would argue that the most important form of liquidity creation is government deficit spending, which is and has been very high and overwhelms every other measure. I also find this view appealing, but if this is right, why not just dispense with all the liquidity talk and say, contentedly, “so long as deficits stay high corporate profits will stay high and the market will rise”?

-

One can build a still more comprehensive, more global account of liquidity. This is what, for example, Michael Howell at CrossBorder capital does. He thinks that while central banks are withdrawing liquidity (not only in the US, but also in Japan, Europe and the UK; China is the exception), there are several offsetting factors. For example: as rates fall, sovereign bond values rise, meaning financial market players can borrow more against them, adding to liquidity. Reinforcing this effect is the fact that bond volatility has been falling (somewhat unevenly) since early August. When bond volatility is low, borrowers need fewer bonds as collateral for loans.

-

We could argue that the effect of liquidity is damped right now because there is low velocity of money in the financial system. That is, there is a lot of cash around, but it is just sitting there in money market funds earning a decent yield, rather than chasing risk assets. This theory would imply that as rates and cash yields fall, the liquidity effect on asset prices will reassert itself. But unless you have a good measure of velocity of money within the financial system specifically (as opposed to velocity of money in the economy in general, for which there are standard measures) then this is just hand-waving at something that sounds like “animal spirits” or “greed.” And if sentiment is the decisive factor, we should just talk about sentiment.

Which of these approaches do readers prefer? Are there others? Or should we abandon the liquidity theory altogether?

One good read

Nothing is something.

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.

Recommended newsletters for you

Due Diligence — Top stories from the world of corporate finance. Sign up here

Chris Giles on Central Banks — Vital news and views on what central banks are thinking, inflation, interest rates and money. Sign up here

#measure #liquidity