How luxury priced itself out of the market

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

That luxury goods have a value proposition at all may be news to many. Consumers are quick to decry greedflation when the price of supermarket staples rises faster than the cost of raw materials. But when one is already paying silly money for a handbag or a watch, it is difficult to understand when too much becomes too much. Yet for all that, there are convincing signs that the luxury sector’s post-pandemic price rises have dented its appeal.

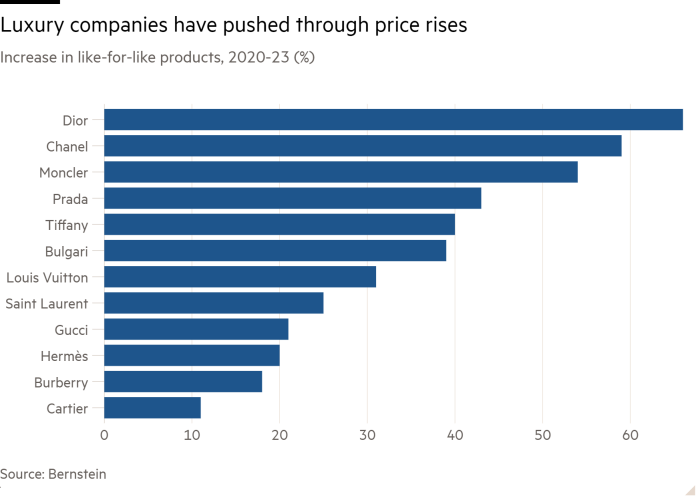

Bernstein analysts estimate that, between 2020 and 2023, global like-for-like prices on a selection of “evergreen” products rose 66 per cent at LVMH-owned Dior, with Chanel hot on its tail. At the other end of the spectrum, industry leader Hermès restrained itself to a 20 per cent increase.

This trend has been responsible for much of the sector’s margin expansion over the past few years. Operating profits rose from 21 per cent of revenue in 2019 to 26 per cent in 2022 on HSBC numbers. Trouble is, it is now unravelling. With consumers tightening their belts, pricing has gone from being a tailwind to a headwind.

Already, many brands have stopped upping their price tags. Some have even gone into reverse. And brands do not necessarily need to discount to see lower margins. They just need to introduce more of the cheaper entry-level products. Overall, the second quarter saw a 3 per cent decline in the average selling price of luxury products and a 6 per cent decline in the price of handbags, according to Bernstein analysis of Lyst data.

Not all brands will be equally affected. Hermès, which combined restraint with desirability, managed to push through an 8 to 9 per cent increase in the first two months of the year, according to HSBC. Moncler and Prada — among those that increased prices most sharply post-pandemic — have done so from a lower base. Recent performance suggests that they have not — as yet — managed to price their customers out of the door. Conversely, Burberry had been relatively conservative in its traditional product line. But new collections have been vastly more expensive, driving a 21 per cent volume decline in the second quarter of the year.

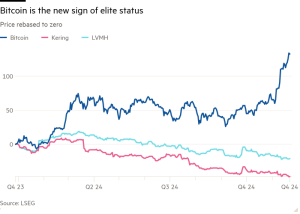

Overall, declining pricing power suggests that the much-awaited luxury renaissance will be a long time coming. Investors have bid up the sector more than 10 per cent on hopes that China’s stimulus package will revive its fortunes. It will not be that simple.

#luxury #priced #market