A conscious way to shop for beauty

Ask people whether or not they value ethically made beauty products and the answer will be a resounding yes. Who doesn’t want to do better for the good of the planet? But information on the environmental and social impact of brands is scarce, making it trickier for consumers to shop with confidence. Seeking to solve that conundrum is Good On You, a platform that assesses companies on their value chain and provides a rating from 1 (avoid) to 5 (great). And after nearly a decade of analysing fashion brands, it’s expanding into beauty.

The move into beauty is largely driven by customer demand, says Sandra Capponi, who co-founded Good On You with Gordon Renouf in 2015, in the wake of the Rana Plaza collapse two years earlier, in which over 1,100 people (mostly garment workers) in Bangladesh lost their lives. That sparked a swell of consumer interest in shopping more consciously and ethically, says Capponi. “From the beginning we wanted to help consumers make more informed choices. It was always part of our ambition to move beyond fashion.”

The beauty industry’s supply chains, Capponi says, require just as much — if not more — transparency than other sectors, “because [the products are] so personal. It literally goes on our skin. There are direct health impacts that have driven movements around beauty that is clean, natural, organic and cruelty-free. But what do these terms really mean? How do consumers know whether ‘clean’ means it’s good for them, or the environment? There is a lot of murkiness and that’s why we’ve stepped in, to encourage more transparency and conversations between people and the brands they are buying from.”

Enter Good On You’s new beauty vertical, which provides a system for scoring brands, based on up to 1,000 environmental, social and governance data points from publicly available figures, parent company reporting, beauty certifications and standards, and third party indices and reports. They’re compiled by an in-house team — there are 30 employees globally — that works with external professionals, academics and non-governmental organisations, according to Capponi, including the Global Shea Alliance, Upcycled Beauty Company and Responsible Mica Initiative.

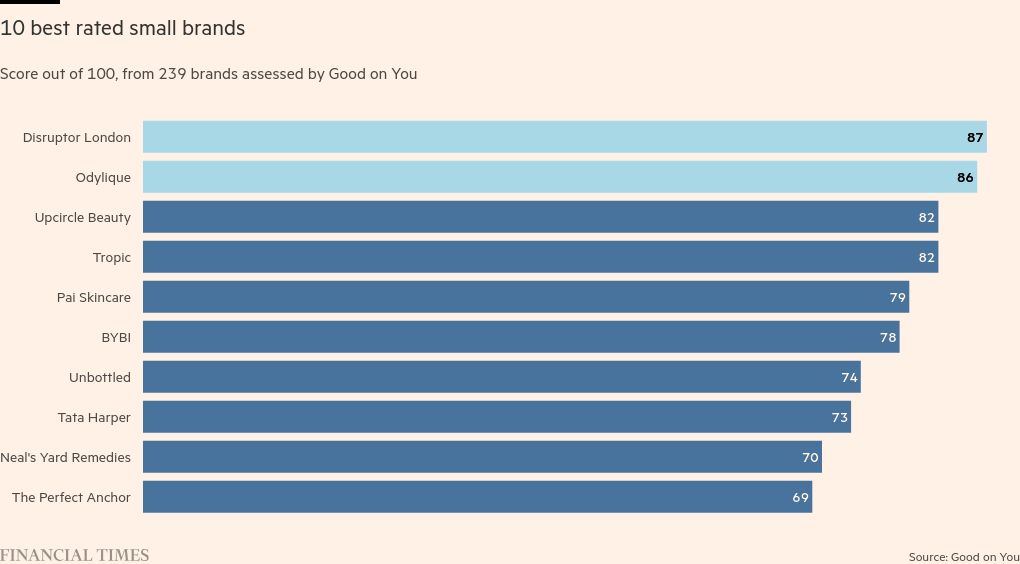

The findings are intriguing: of the 239 beauty brands reviewed by Good On You at launch, Tropic Skincare, Pai Skincare, Tata Harper and Neal’s Yard Remedies are among the smaller brands that rate highly (70 per cent or above), while Lush, Youth To The People and Garnier (the latter two are owned by L’Oréal) top the list of best rated big companies. Among the brands that ranked poorly were Laura Mercier and bankruptcy survivors Morphe and Revlon.

Unlike existing household, personal care and cosmetics databases, such as EWG Beauty, Yuka and Think Dirty, which have been gaining steam among younger generations eager to take control and identify potential toxins in legalised products, Good On You does not offer insights on specific items. Instead, it evaluates companies as a whole, looking at ingredients, but also living wages, animal testing, climate reporting and packaging solutions. “We’re looking at the big picture. Product information is important, but that sometimes can be misleading, because [it bypasses] the impact that happens down the supply chain,” says Capponi.

One challenge is the platform’s dependence on the data it is able to accrue. If a company doesn’t disclose its commitments or progress on combating climate change, it will be ranked poorly on Good On You’s platform. Some businesses say they are wary of giving away too much information to a for-profit company; others argue that sharing information can result in a productive but expensive consultation. (Capponi did not disclose the pricing of services, but says that commercial partnerships with the likes of Yoox-Net-a-Porter, Farfetch and Unibail-Rodamco-Westfield are the primary driver of revenue).

“Transparency is a core principle of our rating system,” responds Capponi. “There is a tendency to hide behind trade secrets — that was long a common excuse in fashion — but consumers have the right to know what brands are doing, and they can’t make informed choices if brands aren’t being fully transparent on their practices.” She adds that “transparency is important in driving progress, because brands are more likely to follow through on those commitments if they’re disclosing them to the public.”

While there is a lack of consistency between one rating firm and another, experts believe that disclosure is slowly but surely becoming an avoidable requirement. “The evolving regulatory environment is going to force brands to be transparent about the ingredients in their products, where they were sourced from, and if they can be recycled,” says Accenture’s retail sustainability lead Cara Smyth. Rating apps pose a threat to brands, because “the reputational risk of doing things wrongly could hurt consumer trust. And when that trust is broken, it’s very difficult to restitch.”

Jen Novakovich, founder of The Eco Well, a beauty-focused science communication platform and consultancy, is less enthused by platforms that claim to help shoppers make better decisions. “Consumption is the greatest impact on the environment per capita,” she says. When brands purport to be ‘sustainable’, “customers feel that they can support the environment with their wallets, when what we need are policies that guide corporations to minimise their impact. Consumption is not the answer.”

For Novakovich, companies are better off prioritising a climate policy footprint, such as lobbying for or putting money towards carbon tax. “Few are willing to do this because it’s often going to hurt their bottom line,” she says. “There’s not always a win-win solution when it comes to environmental impact.”

But for now, shopping remains a form of escapism for many people, who simply want to know if a potential purchase meets their ethical requirements, Smyth observes. “Maybe I’ve had a hard day and I want to buy a red lipstick. I think people are feeling overwhelmed with all of the rapid changes and geopolitical risks in the world, and to say that every time we buy something it’s bad because it’s consumption, that layers heaviness on. You want to be part of the solution, but you also shouldn’t lose the joy of beauty and fashion.”

Good On You’s ratings are date-stamped and revisited every 12 to 18 months. The results are not always satisfactory for brands, but Capponi says that it has led to conversations on “how they can improve, because they realise that consumers are accessing this information and using it to make choices.” Misinformation and distrust are among the biggest hurdles for consumers who want to shop more consciously, Capponi says. “Without that transparency, we’re not really able to connect the dots.”

Sign up for Fashion Matters, your weekly newsletter with the latest stories in style. Follow @financialtimesfashion on Instagram and subscribe to our podcast Life & Art wherever you listen

#conscious #shop #beauty