the crisis in English courts

The court system in England and Wales is broken, lawyers and judges have warned.

Decades of underfunding — exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic and barristers’ strikes — have pushed a once-strained system into crisis.

From tribunals to the most serious cases such as rape, court staffing and funding shortages are delaying — and in some cases denying — justice.

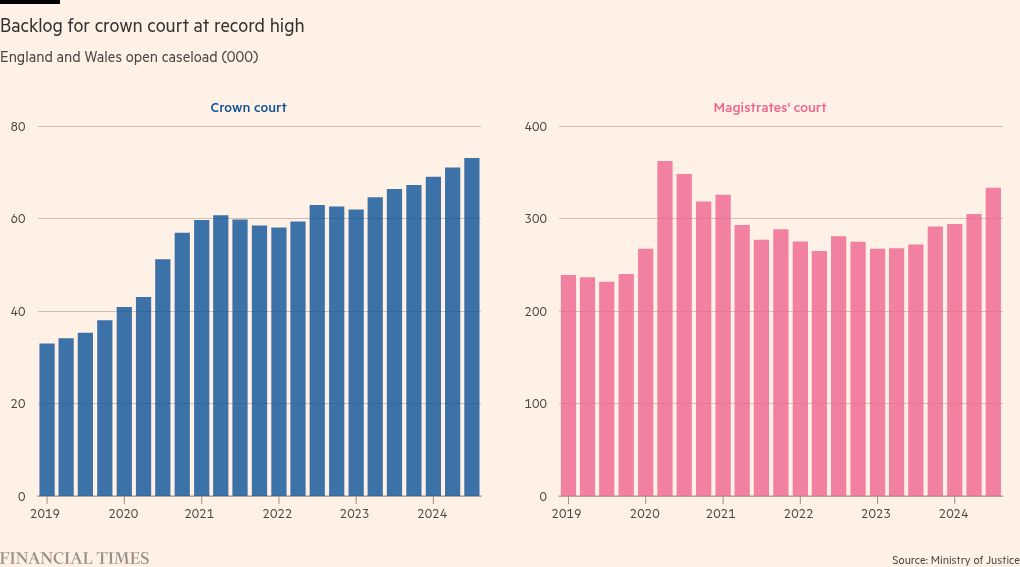

Heavily delayed figures released on Thursday showed that the backlog in crown court cases, the most serious, have nearly doubled since 2019.

“We’ve been saying for years and years: ‘you have a looming crisis’,” said Richard Atkinson, president of the Law Society. “But government after government was happy to effectively play pass the parcel with this time bomb.”

Shortages of publicly funded solicitors, barristers and judges, together with building closures and a lack of court staff, meant “there is not enough capacity in the system to deal with the cases that are going into it”, he said.

The crown court backlog hit 73,100 at the end of September, a record figure that is up from 66,400 a year earlier and 38,000 at the end of 2019.

Courts minister Sarah Sackman KC warned that without action the number of cases waiting to be heard could approach 100,000.

The backlog figures “aren’t just numbers, they represent tens of thousands of people whose lives are on hold”, said Riel Karmy-Jones, vice-chair of the Criminal Bar Association. “That affects and punishes defendants, witnesses and victims of crime equally, leaving them unable to move on.”

On Thursday — as the dismal figures were published — Sackman announced plans for an independent review of the system.

The review led by retired judge Sir Brian Leveson could result in some offences currently subject to crown court jury trials instead being heard by magistrates, which hear less serious cases.

But turning to lower courts is by no means a guaranteed solution.

While it remains shy of a peak reached at the start of 2020, the magistrates’ backlog stands at more than 333,000, up 22 per cent from 272,000 a year ago and 39 per cent higher than the 240,000 reached at the end of 2019.

“We already see that magistrates court list backlog growing — without additional work being pushed in there from the crown court,” said Atkinson at the Law Society.

“By squeezing the balloon at one end, you are going to cause it to swell at the other.”

Magistrates already handle more than 90 per cent of the criminal cases in the justice system, and at lower cost, than the crown courts, giving them potential capacity to absorb some cases that trickle down from the higher courts.

Ministers said Leveson’s review would take any impact on magistrates into account. “No options should be off the table,” Sackman said.

Mark Beattie, national chair of the Magistrates’ Association, said the review “must be supported by a long-term, sustainable and considered investment in the whole criminal justice system”.

Long waiting lists translate into long waiting times.

The average crown court case took 709 days — almost two years — to go from offence to completion as of the end of September. A year earlier, the figure was 677 days.

“No one should have to wait for years for a criminal charge to be brought to trial,” said Karmy-Jones of the Criminal Bar Association.

Stephen Parkinson, director of public prosecutions, warned this month that prolonged wait times risked alienating witnesses and victims.

“It is difficult to keep victims with us,” he said.

There is particular concern about the backlog of adult rape cases, which reached a record 3,290 as of the end of September, an increase of 26 per cent over the past year.

Away from the high-profile criminal courts, lawyers warned that tribunals too were starved of resources, leading to extensive delays in important areas, including immigration and special educational needs.

The backlog in the first-tier immigration and asylum tribunal, which hears appeals against some decisions made by the Home Office, including deportation cases, reached an eight-year high of 62,900 as of the end of September — more than doubling from 30,900 a year ago.

The special educational needs and disability tribunal hears appeals against local authority decisions to deny parents extra resources for their children among other related issues.

The tribunal has faced an influx of cases, driving the backlog to a record 10,500 cases as of the end of September, a more than three-fold rise since 2019.

Tribunals are being “slowed down” in part because more appellants were appearing as litigants in person without legal representation, Atkinson said.

Across the wider system, the lack of capacity is in too many cases making a mockery of British justice, lawyers said.

Karmy-Jones added: “There is no point in talk of investing in police investigations, in arresting more people, in the protection of women and girls, in ‘swift justice’ and building new prisons, if by the time a case reaches trial, there is no one to conduct it, or no court time or space to hear it.”

#crisis #English #courts