Brazil’s fiscal shortfall sends currency plumbing new lows

A panic in Brazil’s financial markets has laid bare plummeting investor confidence in the fiscal policy of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, with his leftwing administration under intense pressure to fortify the public accounts of Latin America’s largest economy.

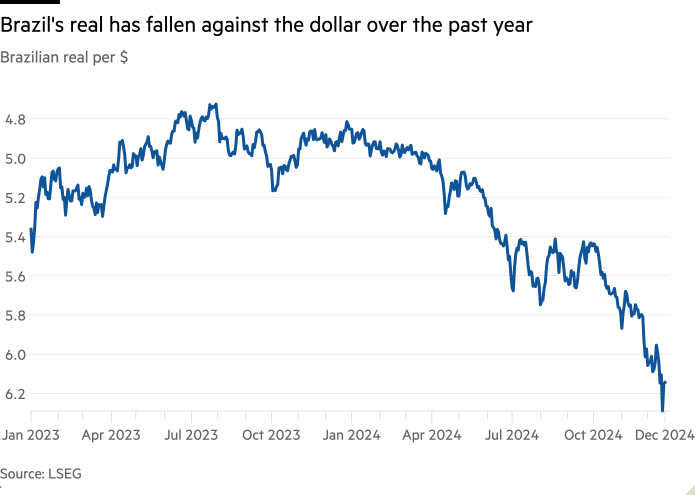

The real dropped to a record low against the US dollar on Wednesday, leading to aggressive central bank interventions to support the currency, in a sell-off that also hit share prices and pushed up government borrowing costs.

“Right now there’s absolute fear in the market, driven by fiscal concerns,” said Edwin Gutierrez, head of emerging market debt at asset manager Abrdn. “It’s not just the real — even in the external [sovereign] bond market there’s contagion. It’s irrational despondency.”

The turmoil reflected worries that not enough is being done to tackle a chronic budget deficit, even as finance minister Fernando Haddad rushed to obtain congressional approval for R$70bn (US$11.3bn) in spending cuts before the festive holidays.

Economists warn that without tougher action, the country’s public debt risks hitting unsustainable levels, with potential negative knock-on effects for inflation, interest rates and, ultimately, growth.

“The lack of meaningful signals on fiscal moderation has thrown Brazil into crisis mode again,” said Mariano Machado at consultancy Verisk Maplecroft.

The episode has presented the greatest challenge for Lula, 79, in his third term as leader. During a first stint from 2003-2010, the former metalworker won plaudits for raising living standards, while largely respecting fiscal orthodoxy.

He returned to the presidency last year promising extra cash for infrastructure, public services and welfare. Unemployment is now at the lowest level since records began and GDP is forecast to expand by a robust 3.4 per cent in 2024.

However, sceptics say the performance has been boosted by excessive government stimulus that is storing up problems. Some in the business world disillusioned with the tax-and-spend agenda are drawing parallels with Lula’s handpicked successor as president, Dilma Rousseff, whose policies were widely blamed for contributing to a deep economic slump.

Under Rousseff, increased expenditure and tax breaks to promote growth caused imbalances that compounded the impact of a global commodities downturn. Brazil’s economy shrank almost 7 per cent between 2014 and 2016, when she was impeached for breaking budget laws.

“We are repeating the mistake made by Dilma’s government, which led to a significant rise in inflation and the biggest recession in our recent history,” said Solange Srour, director of macroeconomics for Brazil at UBS Global Wealth. “The result of the current crisis of confidence is one of the lowest investment rates [recorded in official data] and a very high real interest rate.”

Lula supporters counter the market turbulence belies an economy in good health, pointing to a reduction in poverty and lower inflation than when he took office.

“The only thing wrong in this country is the interest rate, which is above 12 per cent,” the president said last weekend, after being discharged from hospital following emergency surgery for a brain bleed.

The leftwinger has long accused the central bank’s high borrowing costs as a drag on growth.

From January 1, the central bank will have a new governor chosen by Lula — former deputy finance minister Gabriel Galípolo, 42. His appointment has raised questions about central bank independence at a sensitive moment for the institution.

With inflation above a targeted upper limit of 4.5 per cent, the central bank raised its Selic benchmark by 100 basis points this month. Two further increases of the same magnitude are set for early next year.

Members of the government, meanwhile, play down concerns the economy is running too hot.

Guilherme Mello, a high-ranking figure in the finance ministry, acknowledged this year’s GDP forecast was slightly above the economy’s potential, but said overheating will be avoided if a predicted slowdown to 2 per cent in 2025 proves correct.

“Fiscal stimulus fell significantly in 2024 and it will be even less in the next two years,” he added. “Inflation would have been lower if not for climate events like floods and drought. Next year a much better harvest is forecast, therefore a moderation of growth in food prices.”

Officials also insisted serious fiscal adjustment is under way, in line with Haddad’s goal to eliminate a primary budget deficit, which discounts for interest payments on existing debts.

Mostly funded by increased tax receipts, the shortfall is expected to be about 0.5 per cent in 2024, compared to 2.1 per cent in 2023.

Even so, Brazil’s nominal deficit — which includes interest payments — has more than doubled to 9.5 per cent since Lula took office, pushing up public borrowing. Government debt to GDP has risen to 78.6 per cent, relatively high for an emerging nation, and is projected to breach 80 per cent by the end of Lula’s mandate.

“This is a very significant level. It creates great uncertainty as to how the debt will be financed,” said Marcos Lisboa, an economist who worked in Lula’s first administration.

Given more than 90 per cent of Brazil’s budget is allocated to legally mandated items, such as pensions and social benefits, finding major cost savings is very difficult for any government, Lisboa added.

For now, at least, the exchange rate has stabilised, after the central bank burnt through about $17bn in spot market auctions over a week to support the currency. After breaking the threshold of six to the dollar for the first time last month, the real touched 6.32 in recent days — an all-time low since being introduced in 1994 — before recovering to 6.07.

Yet it is down one-fifth against the greenback in 2024, adding further inflationary pressures. While even some traders see a market overreaction, members of Lula’s Workers’ Party allege financial “speculation” aimed at undermining the administration.

“This arm twisting by the market, aided by the central bank, for a hard adjustment in the public accounts is resulting in a negative mood and making the real fall,” the party’s head, Gleisi Hoffmann, told the Financial Times this month. “I believe [the market] has a political plan to make the government unviable.”

Fund managers say the currency’s plunge was fuelled by delays in the announcement of long-awaited spending cuts last month, then worsened by a surprise income tax exemption for lower earners unveiled at the same time.

Haddad said the measure would be funded by higher levies on the rich, but critics saw a populist move that damaged the government’s claims of fiscal responsibility.

Even after its extraordinary market interventions, the central bank retains large foreign exchange reserves — with a stockpile of about $340bn — providing a buffer against currency shocks.

But in financial circles there is a growing belief the government will be forced to draw up new austerity proposals to regain investor confidence. Traders say an emergency rate increase by the central bank might also be an option.

“The market is very pessimistic,” said Leonardo Calixto, co-chief executive of REAG Asset Management. “There are no signals that this can be resolved in the short term.”

Additional reporting by Beatriz Langella. Data visualisation by Janina Conboye

#Brazils #fiscal #shortfall #sends #currency #plumbing #lows