Can things get worse at Boeing?

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every weekday. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

Good morning. Chinese and Japanese 30-year bond yields are almost even with one another for the first time in forever. Evidence that China is Japanifying, or that Japan is no longer Japanified? Email us with your take: [email protected] and [email protected].

Are we there yet, Boeing?

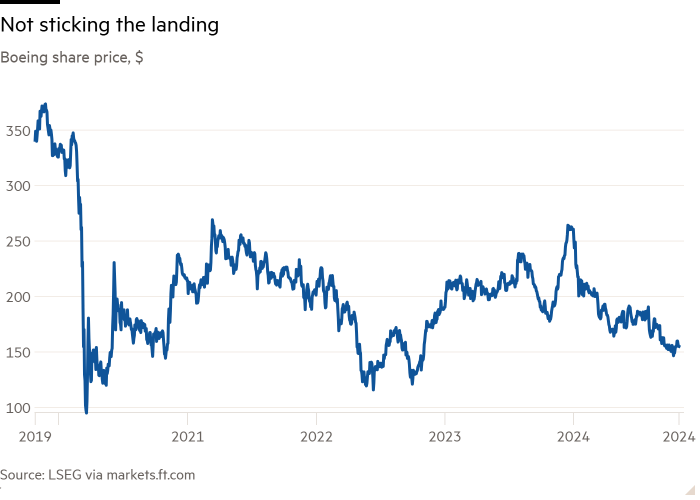

Boeing’s stock price is at less than half its 2019 level. It has dealt with scandal after scandal including, but not limited to, crashes of its 737 Max jets, door plugs falling out mid-flight, and the embarrassing stranding of two American astronauts at the International Space Station. It is not shipping enough planes to cover its rising fixed cost base. Wall Street expects its stock to lose $14 dollars a share this year.

But Boeing is, with Airbus, half of a global duopoly in commercial aircraft. That is why most observers — including Unhedged — assume that it will return to some sort of health eventually. The world needs more than one plane maker. Who else is it going to be? To put the same point numerically, Boeing has a backlog of over 5,400 commercial planes, worth $428bn. That’s about five years of revenue. Analysts expect Boeing will have mostly turned the ship around by 2027, earning $8 per share (roughly the level of 2015 and 2016), and for things to improve further from there.

Regular readers of this newsletter will remember that the last time we wrote about Boeing, about ten months ago, the question Wall Street was asking was whether the company would return to normal profitability, around $10 a share, in 2026. That dream has been given up: consensus for 2026 is now under $6.

The worry is not that Boeing will never be fixed. It is whether the wait will be so long that it is not worth holding the stock today. Let’s suppose the company meets 2027 expectations of $8.25 a share. Put multiple of 20 on that (generous, by historical standards). That makes it a $165 stock a few years from now. The price is now $155. Why bother, unless you see Boeing beating expectations?

To do that, CEO Kelly Ortberg and his team will have to deal with a number of crises. Boeing’s largest union is on strike. At the same time, manufacturing costs are high and rising, and cost cutting and lay-offs are a possibility. The supply chain continues to be bogged down by quality and process issues. Its efforts to strengthen its supplier network is under strict supervision from the Federal Aviation Administration. And there are rumours that it will sell off its struggling space business. Plus, it needs to do all this while investing in the next generation of planes that will keep it competitive with Airbus.

Are things now as bleak as they can get, making this the perfect time to buy? Perhaps not. Boeing’s debt burden and debt service costs are rising. It needs to raise equity, perhaps $10bn worth, to avoid the rating agencies slashing its credit rating to junk, which would make its debt even harder to carry.

Boeing may be fairly valued at $155. But it doesn’t look cheap.

(Reiter and Armstrong)

It’s the growth, stupid

Last week we wrote about the fact that long bond yields were rising and that US stock valuations were rising, too. There was a popular argument of a few years back that stocks — especially “long duration” tech stocks — should rise when rates fall. That argument does not, apparently, work in reverse when rates are rising. As a result, valuation methods that incorporate interest rates, such as Robert Shiller’s excess Cape yield and UBS’ Holt framework, now suggest that stocks are very expensive.

Several of our regular correspondents wrote to argue that we are missing a trick. For stock valuations, it matters why bond yields rise. Here is James Athey of Marlborough Group:

Surely it’s the “why” that matters more than just the direction? Ie, why bond yields are changing dictates the nature and extent of the impact on stock prices. If bond yields are rising because inflation is high and the central bank is about to step on it, then absolutely that should be a headwind for stock prices …

But if yields are rising because growth expectations are rising (but monetary policy isn’t expected to counteract that fully) then the negative effect on multiples via discount rates can be counteracted by the implicitly rising expectations for future earnings . . . I’d argue that latter point is true today — hence why the curve has been steepening and only half of the rise in nominal yields has come from the rise in real yields

Dec Mullarkey of SLC wrote:

Fixed cash flows will price to a lower value at higher rates. That all seems airtight. But the static model fails in practice because it matters as to why rates are rising. If it is because growth prospects are increasing and inflation and price power is picking up, then the equity cash flow outlook should also be improving…

In the charts below [which use data from 1997 to today] you can see the sensitivity (slope of line) is higher for changes in inflation expectations than for changes in real yields.

At a fundamental level, changes in inflation expectations, over the last several decades, have been a proxy for improving growth.

Some guy named Ethan wrote to ask,

Isn’t the simplest explanation for why equity valuations have been robust to rising bond yields just above-trend labour productivity? That would push bond yields up because it means stronger trend growth and a higher R* [neutral interest rate], and it supports valuations through better expected profitability (more output from the same amount of labour cost input, ceteris paribus).

We don’t write for The Economist, so we had to look up what “ceteris paribus” means. Turns out it’s Latin, and means “all else equal.”

Our correspondents’ fundamental point is surely correct. But it is only reassuring if you think that the big run up in yields over the past month or so does reflect higher nominal cash flows in the future; that the economy is heating up and companies still either have pricing power or, as Ethan argues, room to expand margins. It also assumes the Fed won’t have to reverse course. We’d argue all this is very much open to question.

We’d also point out this was not the argument that was made back in the happy days of 2021 and 2022. Back then, rates down meant stocks up, period. There was no discussion of whether low rates reflected lower future growth. Well, that is not quite fair: it was often pointed out that a virtue of the big tech stocks was that they are not economically sensitive, so a weaker economy in years to come does not matter to their earnings growth. And if that is true, and it is also true that now the economy is getting hot that will increase the big tech companies cash flows, then the big techs are a one-way bet on the US economy, and we should all own them, and nothing else.

One Good Read

Wargames

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.

Recommended newsletters for you

Due Diligence — Top stories from the world of corporate finance. Sign up here

Chris Giles on Central Banks — Vital news and views on what central banks are thinking, inflation, interest rates and money. Sign up here

#worse #Boeing