Benjamin Button’s clues for the US economy

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is an economist at Capital Group

As the US economy powers ahead, defying countless warnings of a recession, you may wonder, as I do: how did we avoid this long-predicted downturn? Odd as it may sound, there are some parallels to be found in the 2008 film, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.

Movie buffs will remember that the title character, played by Brad Pitt, ages in reverse — from an old man to a young child. The US economy is on a similar path, reverting to a time of solid, sustainable growth. It is going from a “late-cycle” stage, characterised by tight monetary policy and rising cost pressures, to “mid-cycle,” where corporate profits are growing, credit demand increases, and monetary policy shifts into neutral.

That’s in contrast to the typical four-stage business cycle — early, mid, late and recession — you learn about in Economics 101. Based on my assessment, it’s the first time we have witnessed such a reversal since the end of the second world war. And, the even better news is, this condition signals that a multiyear expansion could be on the way, along with the financial market gains that are generally associated with a mid-cycle environment.

How did this happen? Much like the movie, it’s a bit of a mystery, but the Benjamin Button economy has resulted largely from post-pandemic distortions in the US labour market. Some of the labour-related data was signalling late-cycle conditions. However, other broader economic indicators that may be more reliable today are now clearly flashing mid-cycle. And if the economy is indeed mid-cycle then we may not see a recession in the US until 2028, at the earliest.

This type of benign economic environment has historically produced stock market returns in the range of 14 per cent a year and provided generally favourable conditions for bonds as well. With the US economy growing at a healthy rate — 2.5 to 3.0 per cent is my estimate for 2025 — that should provide a nice tailwind for financial markets. In this mid-cycle of stock markets, sectors such as financials, real estate, materials have traditionally done better.

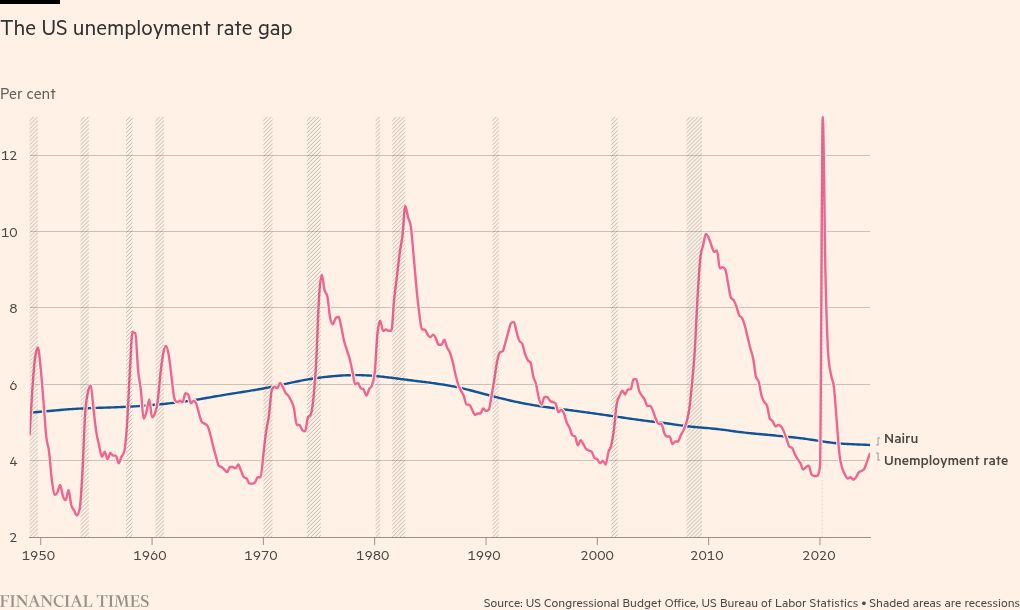

Stay with me for a moment while I explain my methodology. Instead of using standard unemployment figures to determine business cycle stages, I prefer to look at the unemployment rate gap. That’s the gap between the actual unemployment rate (currently 4.1 per cent in the US) and the natural rate of unemployment, often referred to as the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment, or Nairu. That number typically falls in a range from 4 to 5 per cent. Simply put, it’s the level of unemployment below which inflation would be expected to rise.

While this is a summary measure of dating the business cycle, it is based on a more comprehensive approach that looks at monetary policy, cost pressures, corporate profit margins, capital expenditures and overall economic output.

The unemployment gap is a measure that can be tracked each month with the release of the US employment report. The reason it has worked so well is because the various gap stages tend to correlate with the underlying factors of each business cycle. For example, when labour markets are tight, cost pressures tend to be high, corporate profits fall and the economy tends to be late-cycle.

This type of economic analysis also worked nicely in pre-pandemic times, providing an early warning signal of late-cycle economic vulnerability in 2019. That was followed by the Covid pandemic recession in early 2020.

It’s likely that the pandemic has distorted the US labour market, structurally and cyclically. Thus, traditional ways of looking at the unemployment picture are now less useful tools for calibrating broader economic conditions. They’ve become less correlated with classic business cycle dynamics. Not recognising these changes can lead to overly optimistic or overly pessimistic assessments of the cycle.

What does this mean for interest rates? Given my favourable economic outlook, I don’t think the US Federal Reserve will reduce rates as much as the market expects. Remember, inflation hasn’t been defeated quite yet. It’s still slightly above the Fed’s 2 per cent target.

Following last month’s 0.5 percentage point cut, central bank officials will be cautious about future rate cut actions and may proceed carefully in the months ahead. With overall economic conditions reverting backwards rather than forward, there is a new plotline for investors to follow.

#Benjamin #Buttons #clues #economy