How each country’s emissions and climate goals compare

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The Financial Times has created a searchable dashboard of 193 countries’ historical emissions and future climate targets, providing information on the energy mix that indicates their progress on renewable energy.

The database is in its fourth iteration, after being first published at the time of COP26 in Glasgow. It uses data from Climate Watch, the International Energy Agency and the UN’s NDC data registry. Ahead of COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, we have once again updated the interactive.

Legally-binding country targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions are formally called nationally determined contributions (NDCs) and are recorded on the UN global registry.

These national commitments are required to be updated by February 2025, when more ambitious targets will be needed in an attempt to limit the global temperature rise ideally to 1.5C since pre-industrial times, or to well below 2C, as first agreed under the Paris accord in 2015.

Already the long-term global average temperature rise is at least 1.1C, according to the UN IPCC body of scientists report in 2021. This is measured over a period of decades.

Measured over the past year alone, the temperature rise is on track for a rise of 1.5C. The latest UN report warned that the world was on course for a “catastrophic” rise of more than 3C by the end of the century, and that the ability to remain with the target of 1.5C of global warming “will be gone within a few years” without rapid action.

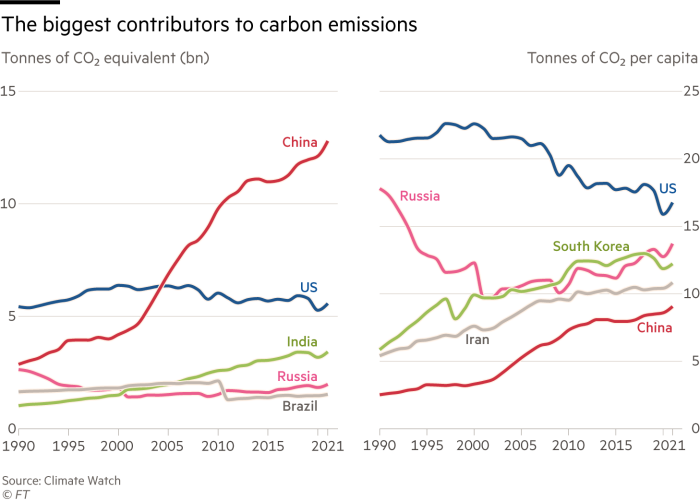

China remains the world’s biggest annual emitter despite a surge in renewable energy development. This is because it remains heavily reliant on coal for power, with 62 per cent of their electricity production in 2022 coming from this source.

It has set a goal for CO₂ emissions to “peak before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060”. It has pledged to track and detect leaks in methane, which holds more warmth than carbon dioxide but is shorter lived in the atmosphere, and is regarded as the quickest way to limit global warming in the near-term.

China accounts for 27 per cent of the world’s CO2e emissions, followed by the US, India, Russia and Brazil. Combined these five nations account for half of the world’s annual emissions.

The US, the biggest emitter on a per-capita basis, saw an increase in its year-on-year emission figures and has once again failed to improve its target in the past year. The Biden administration in 2021 set an economy-wide target of cutting net emissions by 50 to 52 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030.

The third biggest annual emitter, India, is struggling to make headway, after setting a goal in 2022 to reduce its emissions intensity by 45 per cent by 2030 compared with 2005 levels.

Emissions intensity is a goal that is criticised by climate experts because it allows for a rise in absolute emissions, as it measures emissions as a proportion of output.

The choice of different baseline years by country is another of the complexities in setting targets, making direct comparisons difficult. Baseline years often coincide with historical peaks in national emissions.

The less stringent measure of carbon intensity is also used by developing countries to design targets that allow for growth. It is calculated per unit of GDP, to take into account the rise of emissions through economic expansion. China and India use carbon intensity.

Only four countries — Panama, Madagascar, Namibia and last year’s host the UAE — have submitted updated NDCs by the start of November. Azerbaijan, Brazil and the UK are expected to submit their updated climate targets at COP29.

The UAE has said it will cut emissions by 47 per cent by 2035, but this headline target is misleading “as it excludes exported emissions and includes offsetting,” according to analysis by 350.org and Oil Change International. Exports account for 63 per cent of all of UAE’s crude oil.

The oil-rich nation is also expected to increase oil and gas production by 34 per cent by 2035. These plans are not in keeping with the 2015 Paris Agreement.

The COP29 host Azerbaijan also has plans to increase production, and its climate goals have been deemed “critically insufficient”.

Forty-four per cent of Socar’s production will be new oil and gas by 2050, the second highest of any national oil company in the world, according to a report by campaign group Global Witness based on analysis of data from independent consultancy Rystad Energy.

Azerbaijan has said it is “actively working on its updated NDC in line with the 1.5C goal” of the Paris agreement and it will incorporate “ambitious targets”

Follow @ftclimate on Instagram

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here

#countrys #emissions #climate #goals #compare