Britain is being stalked by the spectre of stagflation

Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the UK inflation myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

The writer is a distinguished fellow at Chatham House and a former member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee

Businesses around the UK are calculating the impact of last month’s Budget on their plans for 2025. And the picture is not pretty.

For labour-intensive enterprises such as restaurants and shops, their business-as-usual costs will increase dramatically thanks to higher national insurance contributions, the rise in the minimum wage and rising business property rates. Some of these companies will be able to increase their prices to remain profitable. Others face too much competitive pressure or consumer resistance to do so.

For these, laying off workers, especially part-timers, may be enough to stay in business, albeit at the cost of lower output and rising unemployment overall. And for many companies, profit margins are already very thin and closure is a distinct possibility. What the CBI calls a “triple whammy” of increased costs will erode profitability and thus the confidence and ability of companies to undertake the investment that the government hopes will increase growth.

Such a combination of lower output, higher unemployment and cost-push inflation is the classic definition of “stagflation”. It presents a tough challenge to a central bank focused on inflation targeting. On the one hand, it should tighten policy by increasing interest rates to contain the second-round impacts of rising prices. But on the other hand, it will feel political pressure to keep interest rates low — or even cut them — in order to ease borrowing costs and thereby assist businesses and mortgage holders in the short term.

The risk of this latter route is that it encourages excess debt, which itself is likely to raise longer-term interest rates and borrowing costs. The public’s inflation expectations may also become detached from the central bank’s target, making it harder to achieve.

Exactly this conundrum faced central banks across the developed world in 2021-22 when they judged the inflationary push from the post-pandemic bounceback and higher energy prices after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to be “transitory”. They began with small rises in interest rates until it was obvious that higher inflation had become embedded and stronger action was necessary.

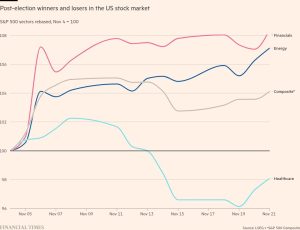

The result was an inflationary surge with damaging economic and political consequences that are still reverberating. Incumbent governments lost elections and consumers are still suffering, including in the UK where food prices remain 25 per cent higher than two years ago.

Yet it appears that neither central banks nor governments have entirely absorbed the lessons of the past four years. In the US, the Federal Reserve is expected to continue cutting rates towards its proclaimed “neutral” nominal level of around 2.5 per cent. This may be the long-term equilibrium level for neutrality, but inflation dynamics operate over the shorter time horizon of one to three years.

The Fed, therefore, needs to re-examine its plans in light of Donald Trump’s election victory. His promises to raise tariffs on imported goods, shrink the labour supply by deporting undocumented immigrants and loosen fiscal policy via tax cuts will all increase inflation. The Fed should counteract these new pressures by holding rates high, even in the face of political pressure to do the opposite. The bond markets will be paying close attention.

In the UK, the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee has judged that the current policy rate of 4.75 per cent is “restrictive” so further cuts are in view. But this depends on the assumption that service sector inflation — currently running at 5 per cent — will diminish, even as the sector’s input costs increase.

The recent Budget shows that public sector spending is set to go up by £70bn, including the wage costs of the government’s recent settlements with the public sector unions. According to the Office for Budget Responsibility, this will add £28bn to government borrowing, even after tax increases. It is unlikely that higher economic growth will come to the rescue as long as the profitability squeeze on the private sector erodes its confidence and ability to invest. And alongside these domestic pressures, there are the external risks of higher energy prices due to the Middle East and Russia-Ukraine conflicts, and new tariff threats from the US.

The MPC already expects inflation to rise moderately in the next few months. But it now needs to reconsider the future trajectory of policy and to recognise this new, and unwelcome, stagflation scenario. The risks of a resurgence in inflation are too great to continue cutting interest rates while inflationary pressures are so strong.

#Britain #stalked #spectre #stagflation