Where I write . . . John Banville’s place of ‘happy nothingness’

Many years ago I spent a week at the Tyrone Guthrie Centre at Annaghmakerrig, near the splendidly named town of Newbliss, in County Monaghan. The centre, which describes itself as “a residential facility for creative artists”, is housed in a grand old mansion willed to the state by Sir Tyrone Guthrie, a mid 20th-century theatrical impresario. It stands on an eminence above a wooded lake, in a situation of great beauty and serenity.

I was allotted the attic room, which has what must surely be the best view in all the house — vast sky, still water, still trees, a Yeatsian flock of swans. My work desk faced the window. On the first morning I set out my writing materials, my dictionary, my antique pocket watch which goes with me everywhere. All set, ready to go. I waited. No words came. I knew, of course, what the matter was: the view, its loveliness not to be borne. With much effort I turned the desk to face a blank wall. Now I could work.

Some people are able to write anywhere — a novelist I know can write on a transatlantic jet. Not I, alas. I must have silence, my empty wall, the happy nothingness that not even the ticking of a venerable watch can penetrate or disturb.

Over the years I have had to put up with numerous discommodings. I recall with a vestigial twinge of discomfort what I believed to be a sea captain’s scarred and rickety desk attended by an impossibly squeaky revolving chair, which I liked to fancy the old salt had sat in while charting his way back and forth upon the bounding main. We had at the time an infant and a Labrador pup. Often I would be compelled to look after the two of them, the dog gnawing my right ankle and the child reaching through the bars of his playpen to grasp me by the soft part of my left calf, and laughing.

Somehow, I managed to write a book.

Then there was the tiny attic room, a chambre de bonne, I imagine, above the garage of a rented house on La Vista Avenue, not some stretch of tawny Californian coast, as the name would suggest, but in an Irish seaside suburb. Mind you, there were palm trees, the survival of which among the mists and gales of an Irish winter filled me with awed admiration.

And then there were the four months I attended the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa, way, way back. I arrived at the end of August into temperatures above 40C all day and halfway into the night, when my brain felt as if it were being broiled. However, the fall — what a beautiful word for autumn — was cool and resplendent, and at last I could work.

If I can call it work. I wrote a novella, in a handsome cloth-bound notebook, which on the day after my return home I shoved into the wood-burning stove in our kitchen and watched through the little smoke-fogged window, with vindictive satisfaction, as the covers buckled and the pages writhed in agony and crumbled softly into ash. Why did I destroy the product of four months of hard labour? Because it was not real; because it was written somewhere else, out of time, out of place.

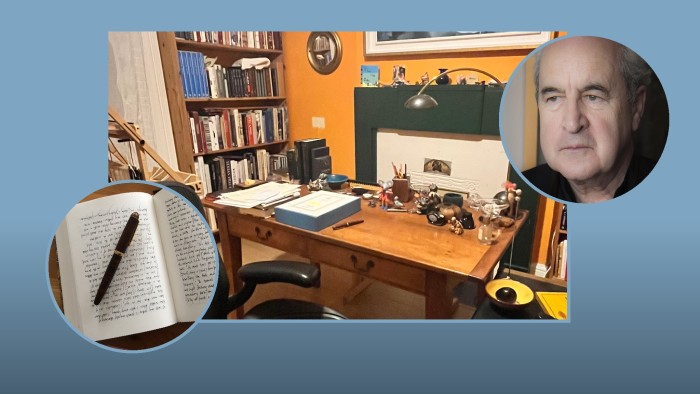

But at last, in these latter years, I have made landfall, like my imagined old sea-dog, in Howth, a fishing village 10 miles north of Dublin city. This room in this house above the harbour will be my final writing place.

Not long ago, someone I love found for me somewhere a splendid second-hand table, which has become My Desk, definitively. It is, compared with the cramped surfaces I used to work on, wonderfully wide and deep — I think of it as an expanse. Which does not mean that I have expanded — no, I remain as cramped and costive as ever, scratching out the unwilling words, “my only loves, not many,” as one of Beckett’s loquacious indigents has it.

Over the years a menagerie of inanimate creatures has accumulated around me; they remind me of the seven dwarfs who in the Disney movie gather to listen to Snow White sing her reedy song about a long-anticipated prince. Among them is a pair of ferocious Chinese dragons, a wooden mouse in a polka-dot frock, an unflaggingly alert stone bird of indeterminate species, and another, smaller mouse, mustachioed, plying a typewriter.

What they make of me it is hard to say, although when I finish work for the day and they crowd forward into focus, I have the impression that they pity me, the poor drudge to whom no prince will come. I suspect they would say of me what Flaubert’s mother said of him, that I have wasted my life on a mania for phrases. But ah, Gustave, such phrases.

John Banville’s “The Drowned” is published by Faber (£18.99)

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ft_houseandhome on Instagram

#write.. #John #Banvilles #place #happy #nothingness