Climate change is a global problem — it requires a global solution

Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Climate change myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

Was the outcome of COP29 a failure or a disaster? To argue that it was instead a success would be reasonable only if we were contrasting the agreement with an irrecoverable collapse (which would, alas, have been plausible, given the return of Donald Trump). But if one ignores this faint comfort, the assessment has to lie between failure and disaster — failure, because progress is still possible, or disaster, because a good agreement will now be too late.

Rightly, the discussions in Baku focused on finance. Almost everybody agrees that hugely scaled-up and cheap financing are a necessary condition for achieving the needed clean energy revolution in emerging and developing countries. Without this, the required investments will not make a commercial return. This is largely because of country risk. Yet, when we are attempting to solve a global problem, which demands a global solution, country risk should be irrelevant. What matters is global returns and so global risks.

In the end, under a deal agreed by almost 200 countries, the rich countries said they would take the lead in providing “at least” $300bn in climate finance by 2035. A member of the Indian delegation rightly complained that “it is a paltry sum”. Indeed, it is too little, too late and still too uncertain.

Two expert groups focused on the need for scaled-up finance have provided somewhat differing assessments: the first views it as a failure; the second thinks of it as a disaster.

In the “failure” camp are Amar Bhattacharya, Vera Songwe and Nicholas Stern, co-chairs of the “independent high-level expert group on climate finance” (IHLEG). They “welcome publication of the . . . COP29 Presidency text on the new collective quantified goal on climate finance”. They note that the text calls on “all actors” to work on scaling up financing to developing countries “from all public and private sources to at least $1.3tn” annually “by 2035”. Moreover, they add, it calls on developed countries to increase their financial support to developing countries to $250bn per year by 2035”. Yet, they add: “This figure is too low and not consistent with delivery of the Paris Agreement.” (See, on this, their “Raising ambition and accelerating delivery of climate finance”, out this month.)

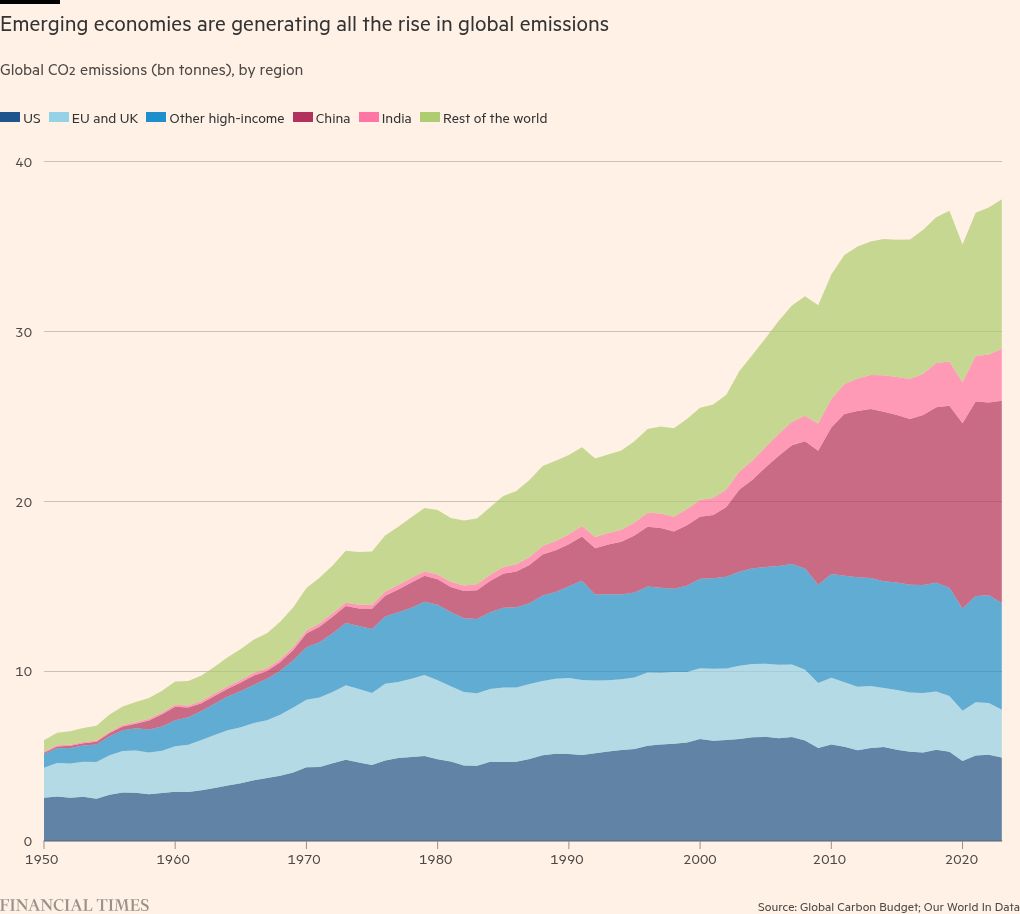

In the disaster camp is a group that includes Johan Rockström of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Action Research, Alissa Kleinnijenhuis of Cornell, and Patrick Bolton at Imperial College (using a paper by Kleinnijenhuis and Bolton). They argue that the world has reached a point of “climate emergency”. Global emissions, they say, must be reduced by 7.5 per cent a year from now on. This would demand a dramatic turnaround from recent trends. It is, therefore, “necessary to mobilise climate finance now — starting at full scale in 2025 — not ‘by 2035’ (or ‘by 2030’ as the Third Report of the IHLEG on Climate Finance suggests”).

Underlying these assessments are differences over the dangers, objectives and political realities. The fundamental point of the analysis by Rockström et al is the overriding priority of keeping the temperature increase above pre-industrial levels to below 1.5C, as set out in the Paris Agreement of 2015. Crucially, they argue, if we blow through this limit, as we are close to doing, we are in danger of crossing four irreversible tipping points: collapse of the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets; abrupt thawing of the permafrost; death of all tropical coral reef systems; and collapse of the Labrador Sea current. All this would put us in a new and very dangerous world.

Moreover, while both groups agree on the priority of finance, the IHLEG quantifies the International Energy Agency’s “net zero emissions by 2050” (NZE) pathway. Both this pathway and that of Kleinnijenhuis and Bolton are intended to limit the temperature increase to 1.5C. But the IEA’s appears to be a little more forgiving. As a result, action under the NZE seems to be somewhat less urgent than Rockström et al demand.

Finally, there are different views of the political realities. Like it or not, the accelerated path desired by Rockström et al, especially the suggested $256bn in annual grants, is not going to happen now. A way must be found round that constraint. Again, the “realistic” choice in Baku was, as noted, between agreeing something inadequate and fighting for something better in future or accepting a collapse of the process.

Yet the insistence of Rockström et al on the dangers is also “realistic”. If we merely pretend to act, the climate will not notice. It is becoming the fashion to treat the findings of science with contempt when we find them inconvenient. But this is no more sane than jumping off the roof of a 10-storey building without a parachute and hoping to fly.

So, what now? The big points on which we should all agree is that stabilising the world’s climate is in the interests of everybody who does not want to live on Mars. Allowing our climate to be destabilised when we have made such progress in developing alternative energy sources seems insane. Installing clean energy across the globe is in the interests of us all. Yet our capital markets are not global, but national. That is a market failure. The solution is for citizens of rich countries to subsidise the country-specific risk of poorer ones. This would require grants (or “grant-equivalent” loans) of some $256bn a year, suggest Rockström et al. Yes, this is a big sum. But it is only just over a quarter of the US defence budget and 0.3 per cent of the total GDP of the high-income countries.

We have long enjoyed the use of our atmosphere as a free sink. It is past time for us to invest in its health, instead.

Follow Martin Wolf with myFT and on X

#Climate #change #global #problem #requires #global #solution