Hot in Hollywood — the fashion designers signing with top talent agencies

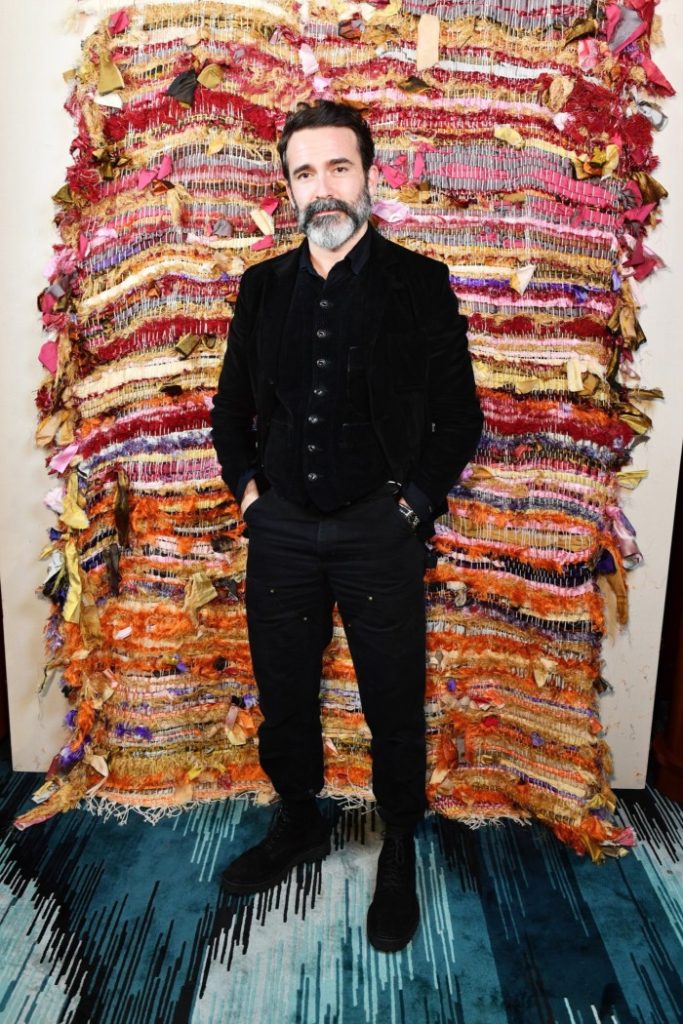

The world of talent management has opened up to include fashion designers, and the latest to join the fold is Jonathan Anderson, the creative director of Loewe and founder of his namesake label JW Anderson. This month, hot off designing the clothing for Luca Guadagnino’s film Queer, Anderson signed with United Talent Agency (UTA), the starry Beverly Hills-based firm that also represents actors such as Timothée Chalamet and Cynthia Erivo.

Except that, unlike Chalamet and Erivo, Anderson is listed under “Fashion”, a division that launched in February 2023 and also includes former Burberry and Givenchy designer Riccardo Tisci. (Anderson is often coy about his future plans — there are rumours over whether he will leave Loewe and take up a role at a larger luxury house — but the signing to UTA speaks volumes about the scope of his ambitions and what he hopes to achieve.)

UTA, which has tapped veteran agent Anne Nelson to oversee its new fashion department, is not alone in seeing the potential of designers beyond their roles in fashion: Los Angeles-based Creative Artists Agency (CAA) represents Tom Ford and Tommy Hilfiger, as well as Schiaparelli’s creative director Daniel Roseberry. (In September 2023 it sold a majority stake to Artémis, the investment company owned by Kering’s François-Henri Pinault). Meanwhile, Colm Dillane of KidSuper and Casey Cadwallader of Mugler are both signed to Hollywood talent agency WME, which this March hired creative strategist Erin Kapor to specifically oversee its creative directors.

The developments mark a shift for talent firms, which have traditionally represented big actors and musicians, who regularly embark on press junkets to promote their films or albums and more recently flog their branded wares. In recent years, representation has expanded to include sports stars and digital influencers, who resonate with Gen Z audiences coming of age as consumers and also influence trends for older generations. Until recently, designers have been largely left untouched. Many working for luxury and fashion brands (as opposed to founders of their own labels) have historically operated behind the scenes, their names not as well known to the wider public. But as the democratisation of fashion grows, caused in part by the endless content created (by both brands and individuals) on and off the runways, that is changing.

After three decades working in fashion communications, in October 2022 Daniel Marks launched an independent London-based consultancy firm, Townhouse, which unlike most communication agencies represents creative talents as opposed to brands. With discretion a primary part of his appeal, Marks is reluctant to name clients (though insiders know that he works with Donatella Versace and Chemena Kamali, Chloé’s creative director).

What Townhouse offers, Marks explains, is “guardianship”, which can range from a “simple holding of hands” ahead of interviews and other personal appearances to “acting as an intermediary between the [talent] and the business”, advising on both commercial and philanthropic projects. A trusted adviser of sorts, you could say — a role that has become crucial amid “huge interest in the personalities behind the brands”, he says.

As the balance of power shifts, individuals have just as much — if not more — influence than the institutions that once presided over them. In fashion, much has to do with the growing responsibilities of the designers; many are now tasked with not only designing a product, but also being the public face of the brand, curating ideas and joining larger cultural conversations. Just look at Louis Vuitton, whose creative director of menswear is the multi-hyphenate musician Pharrell Williams, underscoring its positioning as a cultural brand.

“I think social media has brought about the cult of the individual,” observes Marks. “You see social media stars creating businesses; the Kardashians and Kris Jenner have built fortunes by being a personality first, and then building a brand attached to it second.”

Many of today’s designers are also multidisciplinary. Christian Lacroix and Giorgio Armani set the blueprint for designers crossing into other creative mediums. Lacroix designed costumes for numerous stage productions, including Madonna’s 2004 Re-Invention world tour. Armani’s relationship with film dates back to 1980, when he designed the wardrobe for Richard Gere in Paul Schrader’s American Gigolo. There is also Karl Lagerfeld, whose illustrious career included designing for Chanel while being a formidable photographer. Tom Ford, a designer who built an eponymous empire and is credited with reviving the luxury house Gucci during his tenure there, is also a film director whose 2009 movie A Single Man was Oscar-nominated. And Hedi Slimane is celebrated for his designs for Saint Laurent and Celine as well as for his photography.

“I think there’s a distinction to be made when designers were founders of their own brands. Ford and Armani did step out of fashion quite quickly, but they also had their own brands, and had a certain freedom and independence. That gave them the freedom to explore these things,” says Mariasole Pastori, a talent acquisition consultant who has previously worked with Zegna and Kering. She believes that “these creatives feel the need to step into other disciplines because they often just want to create . . . After years of being pressured to produce collection upon collection [in fashion], it’s refreshing for them to design other things.”

Vickie Segar, founder of the Village Marketing agency that was acquired by advertising giant WPP in 2022, believes that a designer’s influence shouldn’t be underestimated or limited to the companies they work for. “There are brands that are not going to be able to partner with Loewe, but now they can partner with Jonathan directly and that is a really interesting prospect.”

Segar continues: “Jonathan has media reach and a strong personal brand that is creative, luxurious and curated. That’s a powerful combination.” She adds that “across different professions, people are leveraging their [influence] to drive more business”, which in turn creates a halo effect for both the individual and the companies they’re associated with. “What Jonathan is doing is creating not only value for himself but also for Loewe.”

But not all designers want to be famous or operate this way, nor should they (Matthieu Blazy and Peter Copping’s recent appointments as the creative heads of French luxury houses Chanel and Lanvin, respectively, serve as a reminder that more traditional couturiers can coexist alongside multi-hyphenates). However, to build a long-term legacy, designers will need to think beyond simply the collections they design and more deeply about their purpose and where they can make a real difference.

“It’s beyond the selling of clothes or accessories; it’s how this person can use their power to connect with communities and support those who really need their help,” says Marks. But authenticity will always be a requisite. “You can’t drop a designer into a world that they’re not already connected to, because their audience will see it as a cheque-writing exercise. The job in hand will be to ensure that whatever these commercial partnerships look like, they’re intrinsically linked to the passions of the creative person.”

Sign up for Fashion Matters, your weekly newsletter with the latest stories in style. Follow @financialtimesfashion on Instagram and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen

#Hot #Hollywood #fashion #designers #signing #top #talent #agencies