Justice for the victims of Assad’s atrocities in Syria

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Bashar al-Assad issued a statement this week, insisting that his flight from Syria was not pre-planned but an emergency evacuation arranged by Moscow. How the Syrian dictator left, however, is of far less concern than how brutally he ruled. What the hundreds of thousands of families of those killed, disappeared, imprisoned, raped or tortured by his regime want to see above all is Assad and his entourage brought to justice for a horrific toll of atrocities over decades.

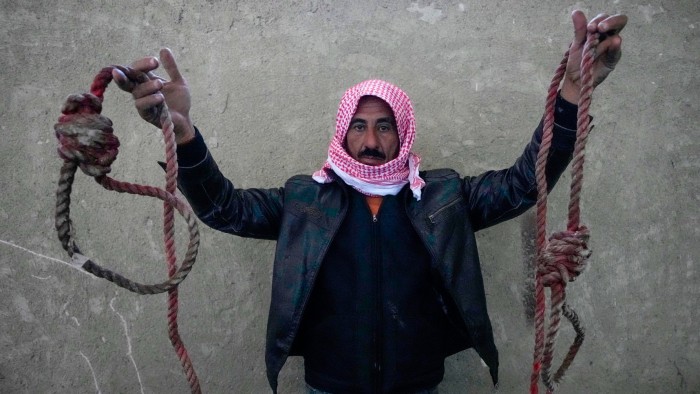

Among the most heart-wrenching videos and accounts since Assad’s overthrow are of gaunt prisoners being freed from the notorious Saydnaya prison and other jails. Families have been roaming cellblocks and combing through files and photos in search of any trace of loved ones.

Syrians deserve justice. But a major complication of the effort to hold Assad, his family and his henchmen to account is that many have already fled. Some top generals and officials have reportedly escaped to neighbouring Arab countries, or gone into hiding in their hometowns.

The immediate priority must be to secure the evidence that can be used to build cases against them over the atrocities carried out during the Assad family’s more than 50-year dynastical rule. The Commission for International Justice and Accountability, a non-governmental body, has already amassed 1.1mn internal documents and testimony from thousands of victims, for use in future trials. The International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism, a quasi-prosecutorial body established by the UN in 2016, has been collecting proof too. But Syria’s interim leadership, which has vowed to bring perpetrators of atrocities to justice, urgently needs to create an independent body to safeguard the documentary trail left behind by Assad’s murderous bureaucracy.

The next issue is where this evidence could be heard. Syria is not a member of the International Criminal Court, and Russia and China are likely to veto any UN Security Council resolution to give the court jurisdiction. An alternative is an agreement with the UN to set up an ad hoc tribunal, similar to those for Sierra Leone or Kosovo, operating under international law. Trials could take place under domestic law, but Syria’s new leaders would have to show they respect the rule of law and form an inclusive, representative administration — and even then the Syrian justice system may lack the capacity and credibility to hear such cases.

One scenario for Syria might be an international tribunal backed by a transitional justice process — following examples in South Africa, Chile and Rwanda — which combines judicial cases with non-judicial measures such as truth commissions intended to promote communal healing.

Even if a process can be set up, could Assad himself ever be brought to trial? Russia’s Vladimir Putin, himself subject to an ICC arrest warrant for alleged war crimes in Ukraine, for now seems unlikely to collaborate in handing over a fellow leader to international justice. But Assad may yet end up elsewhere, and Putin’s regime, too, may pass.

It should ultimately be for Syrians to choose the most appropriate model of seeking legal redress. There are more immediate tasks, including feeding an impoverished people and stabilising government — which is far from guaranteed. Yet some realistic promise of justice for Assad-era crimes may be vital to beginning to build the rule of law. Experience elsewhere suggests the longer legal accountability for atrocities is delayed, the longer it takes for society to come to terms with what took place. Seeing the leaders and accomplices of the previous regime brought to trial must be a key part of Syria’s awakening from its long national nightmare.

#Justice #victims #Assads #atrocities #Syria