South Korea paralysed in fight against Trump tariffs

Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what the 2024 US election means for Washington and the world

South Korean companies fear that President Yoon Suk Yeol’s impeachment following a failed attempt to impose martial law this month has undermined efforts to lobby Donald Trump’s incoming administration to protect their exports and investments in the US.

The US president-elect has threatened to impose sweeping tariffs and review generous subsidies for companies to invest in the US, including those for America’s allies and largest trading partners.

But recent political turmoil in Seoul has left the campaign to counter Trump’s trade protectionism rudderless, according to several people involved in the lobbying effort who described the South Korean government’s diplomatic efforts as “paralysed” and “absent” in the wake of Yoon’s aborted power grab.

“There is no one from the government to represent the Korean interest just when we need it the most,” said a person representing a conglomerate that invested billions of dollars in the US during outgoing President Joe Biden’s term.

“It is not possible for us to withdraw our investments now,” the person added. “We are like in a hostage situation.”

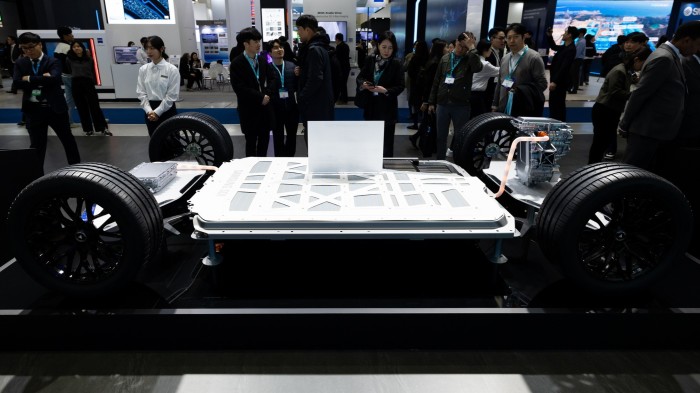

Trump-related risks for South Korea’s export-reliant economy range from across-the-board import tariffs to the possible revocation of subsidies for Korean chip, battery and electric-vehicle makers promised by Biden. The Korean semiconductor industry is also exposed to more aggressive US export controls on China.

The threat of trade disruption also comes at a time when Asia’s fourth-largest economy is already wrestling with weak domestic demand, soaring private borrowing and intensifying competition from Chinese exporters.

On Wednesday, South Korea’s foreign minister Cho Tae-yul acknowledged that the political turmoil had disrupted diplomatic efforts, adding: “We are fully committed to regaining that momentum as quickly as possible.”

Yeo Han-koo, a former South Korean trade minister now at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington, said that even before the political crisis, “the feeling in Seoul could be described as anxiety bordering on panic”.

Korean policymakers and business leaders were “traumatised” by Trump’s first term, said Yeo, when the US president threatened to cancel a bilateral free trade agreement and remove American military forces from the Korean peninsula unless Seoul contributed more to their upkeep.

A survey of 239 companies released by the Korea Enterprises Federation this month found 82 per cent expected South Korea’s economy would be harmed by Trump’s expected protectionist policies.

But Yeo suggested that some Korean fears were “overblown”, arguing that “much has changed” since Trump was first elected in 2016. South Korea was the biggest source of foreign direct investment in the US last year, with companies investing tens of billions of dollars in US manufacturing facilities for chips and green technologies.

“More than perhaps any other country, South Korea can argue it is contributing to a revival in US manufacturing, and that it deserves a place within the walls of Fortress USA,” Yeo said.

South Korea’s trade surplus with the US was $28.7bn in the first half of 2024, according to the Korea International Trade Organisation, and is set to overtake last year’s record of $44.4bn, raising concerns that Trump, who is sensitive to US trade deficits, could target the country again.

However, an executive from one of South Korea’s leading industry associations said that recent conversations with people expected to serve in Trump’s administration suggested that existing investments would do little to sway the incoming president and his inner circle.

“We tried to appeal to them by stressing the fact that Korea was the biggest foreign investor and created lots of jobs,” the executive said. “But we were told that it doesn’t matter for Trump as he is more interested in what the Korean companies will do from now on. He doesn’t want to hear what they did during the Biden administration.”

Another person familiar with the Korean lobbying effort said one “specific concern” was the return of Peter Navarro, Trump’s former trade envoy, as a senior economic adviser.

Trump this month praised Navarro, who previously accused Korean conglomerates Samsung and LG of “trade cheating” by relocating production to avoid antidumping measures, for helping renegotiate “unfair Trade Deals like Nafta and the Korea-US Free Trade Agreement”.

Analysts said Korean companies were unlikely to maintain their scale of investment given the challenges they were already facing, ranging from high costs of construction, labour and childcare to a shortage of skilled labour, difficulties securing visas and reliable power supply. A weak South Korean won and lagging demand for EVs were also dampening enthusiasm.

Lee Tae-kyu, senior fellow at the Korea Economic Research Institute (KERI), said South Korea’s economy could receive a modest boost if Trump’s tariffs focused narrowly on Chinese exports, pointing to shipbuilding, defence and petrochemicals as areas where Korean companies stood to benefit.

Seoul could also reduce its trade surplus by buying more American arms and fossil fuels, Lee added.

But Korean battery and EV makers could face a nightmare scenario if Trump were to reach a grand bargain with Beijing on trade that allowed Chinese rivals to set up their own plants in the US — something the incoming president has said he would consider.

“If Chinese companies are allowed to build plants in the US, that will be a disaster for us,” said a Korean battery industry executive. “But even our government officials don’t seem to know who to talk to in Washington to deliver our concerns.”

#South #Korea #paralysed #fight #Trump #tariffs