Has Sinn Féin missed its chance to govern Ireland?

On a couple of old sofas beside a road outside a disused paint factory north of Dublin, a group of protesters are keeping vigil. Two boys, bundled up against the evening chill, are glued to phones. A man waves a giant tricolour and there are barricades painted in Ireland’s green, white and orange.

A plan to turn the former plant in the suburb of Coolock into much-needed housing for asylum seekers has sparked large, sometimes violent, demonstrations. Anti-immigration protesters say it would bring hundreds of “unvetted” men into a rundown area with already stretched resources.

People in deprived communities such as Coolock feel these tensions more deeply as Ireland, which is likely to call a general election within weeks, is reaping extraordinary wealth from colossal corporate tax receipts paid by multinationals and €14bn in back taxes from Apple.

Sharing that windfall out more equitably is a key pledge of the main anti-establishment party, Sinn Féin. But the protesters on the ground do not see the pro-Irish unity party as a standard bearer for their cause.

“Sinn Féin are too late,” says Shaun Crowe, 34, a spokesperson for the “Coolock Says No” protest. “People are going to be voting for independents and nationalists.”

If they vote at all, that is. “Sinn Féin pretend they back the underdog, but they don’t,” says one of the protesters, a woman who did not want to be named. “I don’t trust anyone in politics — they’re all the same.”

This lack of enthusiasm reflects the latest twist in support for the all-island party once reviled as the political wing of IRA paramilitaries in Northern Ireland’s Troubles conflict, but which today styles itself as a leftist, working-class champion.

Sinn Féin cemented itself as a real political player in the Republic of Ireland in the 2020 election, when it won the most first-choice votes. Having broken into the mainstream with promises to fix the country’s chronic housing crisis, the party then looked as if it could leapfrog the conservative Fine Gael and centrist Fianna Fáil parties that have dominated Ireland’s politics for a century.

The housing issue struck a chord with young voters priced out of housing in the newly wealthy nation, propelling Sinn Féin to a high of some 36 per cent in opinion polls in mid-2022, a share that would put it in position to form a government, if achieved at the ballot box.

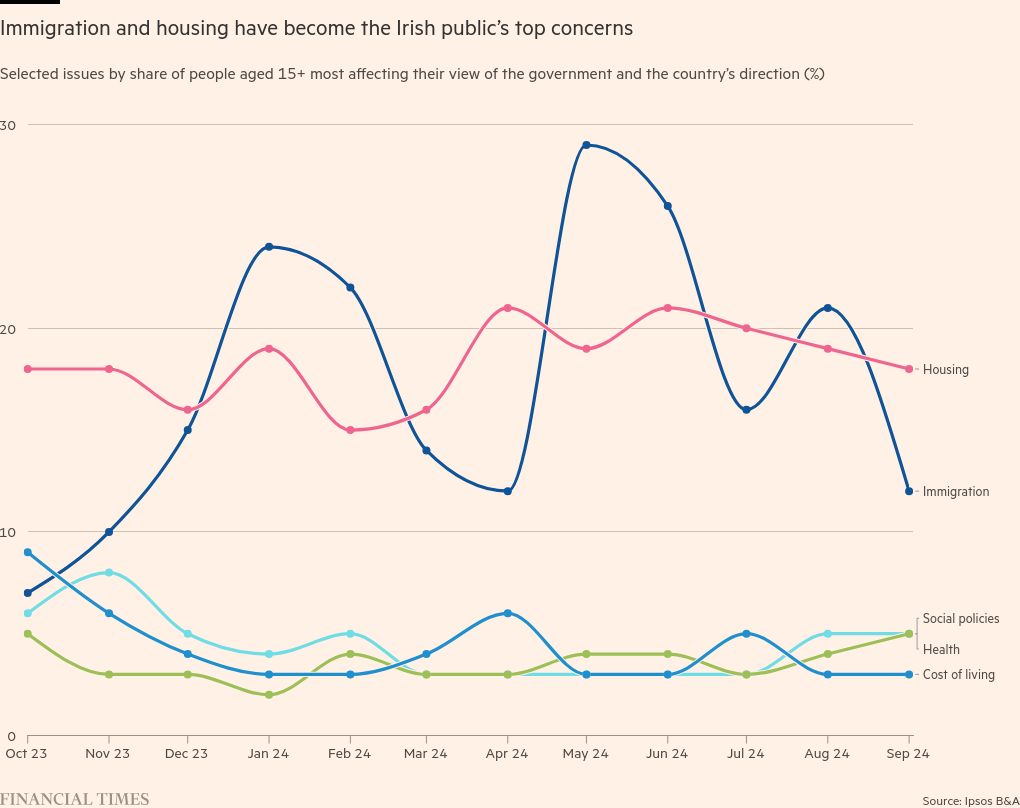

But in recent months, as the number of asylum seekers almost doubled year on year and ugly protests erupted, immigration has emerged as a key concern in a country with no mainstream far-right party.

Sinn Féin struggled to articulate a consistent position on the issue, alienating anti-establishment voters with far-right views who had gravitated towards the party.

Its support in polls has plummeted. In local elections in June, Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil, which together lead the ruling coalition, each scored nearly a quarter of the votes while Sinn Féin performed far worse than expected, sinking to just 12 per cent.

With an election due by March but widely expected next month on the back of this week’s bonanza budget of handouts and tax cuts, Sinn Féin wants to end what it calls the “cosy club” of tired old parties, put reunification front and centre and open a new chapter in Irish politics. But it has a mountain to climb.

Mary Lou McDonald, Sinn Féin leader, is determined. “The challenge set down to us by the Irish electorate was real. We were told: do better. And then advocate more loudly,” she tells the Financial Times.

“So we have to face the challenge full square . . . Our mission is not simply to challenge government failures . . . but also to rebuild confidence that actually, [Ireland’s problems] can be sorted out.”

McDonald, 55, has been at the helm of Sinn Féin since 2018 — only the second leader in the past four decades of a secretive party that still elicits a visceral rejection among some voters on both sides of the border because of what they see as a refusal to condemn past republican paramilitary violence.

A fiery orator and skilled debater, the Dubliner was also the first to have no connection to the Troubles, in contrast to longtime leader Gerry Adams and the late Martin McGuinness, a former IRA commander turned Northern Ireland deputy first minister.

“She changed middle-class attitudes and attracted people who never would have even considered voting for Sinn Féin because she is an acceptable new face without the legacy baggage her predecessors . . . carried,” says Mandy Johnston, a former Fianna Fáil government press secretary.

Sinn Féin is now the most successful party in Northern Ireland, holding the post of first minister in a region that was expected to be part of the UK forever when it was created by partition more than a century ago. In the UK general election in July, it became the region’s biggest party at Westminster too, even though its MPs do not take their seats because they refuse to swear allegiance to the crown.

But putting Sinn Féin in power both north and south could be a tall order. Politics in the Republic have been radically shaken up after former premier Leo Varadkar unexpectedly quit and Simon Harris, a shrewd young Fine Gael minister, succeeded him as the country’s leader in April.

The savvy “TikTok taoiseach” has travelled indefatigably around the country, tapping into the concerns over immigration by clearing Dublin streets of makeshift camps of asylum seekers and posting blow-by-blow accounts of his actions on social media under bold headlines like “delivery”.

The 37-year-old has galvanised a tired-looking party that had been limping towards defeat. “Simon Harris is walking on water,” says Shane Ross, a former independent transport minister and author of a book about McDonald. “Sinn Féin peaked much too early. Mary Lou looks like a busted flush at this stage — I don’t think she’s the asset she was.”

Even insiders admit McDonald has been off her “A” game after a personal annus horribilis that began as the party began to slide in the polls last year.

She took a three-month leave of absence after a hysterectomy to remove tumours in June 2023. As she was recovering, her husband was suddenly taken ill and almost died on a family holiday in France; after emergency treatment for a burst bowel, he was diagnosed with cancer — events she only revealed last month.

Then, only a few months after its local election drubbing, McDonald’s father, with whom she had a difficult relationship, died.

“Knocked off balance” by her terrible year according to one Sinn Féin insider, McDonald’s recent candour about her family was a deliberate move as Sinn Féin seeks to reconnect with voters and recover its mojo.

Prompted by the local election result, McDonald says Sinn Féin “spent this summer putting in a very long shift” to analyse what went wrong and how to fix it. She says she is now fully re-energised and focused but admits: “I think it’s a work in progress.”

The party is sticking to its core promise of “change” but is increasingly talking about fairness in a country with an expected budget surplus this year of €24bn. Unlike in the UK, where welfare is index-linked with inflation, “[benefits] have not kept pace with prices since 2020”, says Barra Roantree, assistant professor in economics at Trinity College Dublin.

Yet analysts say they must walk a fine line. “If they promise the Earth, Moon and stars, everyone says they are cheap populists. If they do anything less, they are vulnerable on the left,” says Brendan O’Leary, professor of political science at the University of Pennsylvania.

Many middle-class Irish in fact feel better off than before, especially after this week’s pre-election budget, which included €2.2bn in cost of living support — some of it, like energy credits and a child benefit bonus, paid universally regardless of income.

“Many wonder why Sinn Féin has slipped so badly in the polls but something that is often missed in the discussion is not really about Sinn Féin at all,” says Johnston. “Despite all the issues like housing and health, most people actually feel better off now than they did two years ago . . . the government has been throwing money at people hand over fist.”

As John Wood, 42, a retail manager puts it: “The government must be doing something right to have all this money.” He says he would opt for the incumbents over Sinn Féin. “Better the devil you know,” he says.

But McDonald believes Ireland’s struggling services and inequalities will prove a real concern for voters. “The real conundrum for a state that has unprecedented resources, wealth at our disposal . . . [is that] the country still feels very far behind,” she says.

Nowhere is that more evident than in Ireland’s housing crisis, the issue Sinn Féin made its own in 2020 and which the party hopes will again prove its trump card.

In Ireland, one in eight households is a millionaire on paper, yet the country also has record homelessness. Insufficient housing supply has pushed prices 6.2 per cent higher on average than a year ago and sparked the highest premiums paid over the listed price of property in nearly 15 years.

The government touts a surge in home construction and expects 33,450 homes to be constructed this year but the central bank warned last month that 52,000 homes would need to be built a year for 25 years to meet both pent-up demand and that of Ireland’s fast-growing population.

Sinn Féin has renewed its pitch with the promise of “A Home of Your Own” in a country where the median age of first time buyers is 39. If elected, it says it will build 300,000 homes over the government’s first term, with an emphasis on social and affordable housing.

“We have produced a very comprehensive five-year [housing] plan . . . it represents the only plan that will actually get to grips with the crisis we’re facing,” McDonald says. “The government has produced targets and plans and rhetoric and sounds and noise and fury — but they haven’t produced any kind of meaningful results.”

But McDonald sparked panic when she told The Irish Times that average house prices in Dublin should fall to “the €300,000 mark” — more than €100,000 below the market. McDonald insists she was referring to the party’s affordable housing plans.

The party has also toughened its rhetoric on immigration, which remains one of voters’ top concerns. In July it unveiled a plan including a commitment not to put asylum seekers in areas already struggling to meet the needs of their populations.

“That did rouse my interest,” says Brian, 48, a retail manager, outside a leisure centre across the road from the “Coolock Says No” protest. But he is not convinced. A leftist who has voted for Sinn Féin before, he says the party “just needs to get themselves a little bit more together . . . I think maybe new leadership”.

McDonald came across as tetchy when explaining the party’s blueprint for housing asylum seekers on national radio, compounding its difficulty in resonating with voters. She drew criticism from the other side for her calls for the justice minister and police chief to resign after unprecedented riots last year.

“They were always clearly a leftwing party, but their support was very diverse,” says Rory Costello, associate professor of politics at the University of Limerick. “That was always going to be a problem because they weren’t going to be able to adopt a position that would satisfy all their voters.”

His analysis of data from the National Election and Democracy Study conducted by Ireland’s independent electoral commission found that “people who formerly supported Sinn Féin and cared about immigration now really don’t like them — so I think it will be hard to win them back”.

At Sinn Féin’s annual party conference in the central city of Athlone last month, the speeches were rousing.

“Our opponents think we are on the ropes. Fine Gael think they are going to waltz back into government, propped up by Fianna Fáil and independents,” thundered Matt Carthy, the party’s foreign affairs spokesperson. “Well, I think they’re in for a shock — we are at our best when our backs are against the wall.”

Sinn Féin has been in the doldrums before. In February 2019, it lost half its council seats in local elections and two of its three MEPs in European polls. A year later, at the last general election, it staged a remarkable rebound to end just one seat behind Fianna Fáil.

But the party has suffered some embarrassing lapses of judgment: one former councillor is now in prison for facilitating murder. In Northern Ireland, two press officers resigned last month after providing references for a former colleague who has since been convicted of sex offences.

Worryingly for the party, an Ipsos poll last month for The Irish Times found a stark fall in support among people in their mid-twenties to mid-thirties. But Costello, at the University of Limerick, says that could also represent an opportunity to build back support, as young voters tend to be less set in their ways.

McDonald had no real explanation for the trend, saying only: “We have to go out and talk to them and engage. That’s a job of convincing that we have to do to catch people’s attention, spark their imagination again.”

She insists she feels the same momentum as in the run-up to the 2020 election, but her personal popularity ratings dropped six points in the latest Ipsos/Irish Times poll, while Harris, the prime minister, surged 17 points as Fine Gael has opened up a wide lead over other parties.

Sinn Féin may, however, take comfort from the finding in the same poll that nearly a quarter of voters would still like to see McDonald as taoiseach after the election, and from its snapshot of voter concerns. Housing comes top and controversy over a bike shed for parliament that cost €336,000 to build — which McDonald says epitomises coalition recklessness — is winning as much attention as immigration.

The party insists Irish reunification is one of its voters’ core values and McDonald remains committed to pushing for a referendum on the issue by 2030.

Attending the UK Labour party conference last month, she called for “not a mere ‘reset’ but a transformation of British-Irish relations” to “acknowledge that [constitutional] change is in motion”.

But no one expects that issue to be a defining one in the coming campaign. Analysts expect it to make up some lost ground and the party knows it faces what the insider called a “dogfight” to “earn votes”.

Johnston, the former government spokesperson, says Sinn Féin could claw back some support “if they lose the hubris they had in the local elections, get the younger vote out and put into effect the machine that they mobilised in the 2020 general election campaign”.

Evie, a 19-year-old film student in Dublin, says she probably would vote Sinn Féin “because of Mary Lou — I think she’s trying to make a change.”

But Chris Gibson, 71, who volunteers in Sinn Féin’s shop in Dublin selling books and republican souvenirs, was under no illusion about the challenges of going up against a government awash with cash.

“With money, governments win wars and elections,” he says. “I hope I’m wrong. But it’s going to be very hard.”

Data visualisation by Oliver Hawkins and Clara Murray

#Sinn #Féin #missed #chance #govern #Ireland