Will AI ‘compress’ the 21st century?

Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Artificial intelligence myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

Rumours of humanity’s demise may have been greatly exaggerated, it seems. Some of our AI overlords, who for the moment remain flesh-and-blood beings rather than robotic terminators, now appear to be retreating from the industry’s more extreme fear mongering.

Over the past year, the so-called doomers, who predicted that a rogue superintelligence might pose an existential threat to humanity, have received plenty of airplay. Their alarmism even prompted the British government to host an international AI safety summit at Bletchley Park last November. But several of the top AI leaders are now tamping down the fear factor and turning up the volume on hope and hype. Eye-rolling sceptics might note that this renewed burst of techno-optimism coincides with big fund raises by leading AI start-ups as they continue to pour billions of dollars into developing their models.

Last month, Sam Altman, the co-founder of OpenAI which has just raised a further $6bn from investors, posted an article entitled “The Intelligence Age” in which he forecast that AI would lead to astounding triumphs: “fixing the climate, establishing a space colony, and the discovery of all of physics.”

Much celebration in the industry greeted the award of two separate Nobel Prizes for physics and chemistry to two teams including the AI pioneers Geoffrey Hinton and Sir Demis Hassabis. Hassabis, the cofounder of Google DeepMind which developed the AlphaFold system that has modelled 200mn protein structures, has talked excitedly about AI enabling science at digital speed.

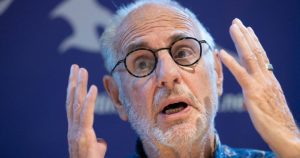

But perhaps the most intriguing demonstration of the switch of mood comes in a 15,000-word essay, “Machines of Loving Grace”, posted this month by Dario Amodei, co-founder of Anthropic. “Fear is one kind of motivator, but it’s not enough,” he writes. “We need hope as well.”

In his essay, Amodei acknowledges the dangers of AI but focuses on the transformative potential of a superintelligence, which he claims might arrive as soon as 2026. Such powerful AI, which he compares with a “country of geniuses in a data centre”, could dramatically accelerate progress in many fields. These breakthrough innovations would “compress” the 21st century. “I think that most people are underestimating just how radical the upside of AI could be,” he writes.

In upbeat mode, Amodei argues that AI could greatly speed up the rate of scientific discovery. This would help us cure many diseases and extend lifespans to 150 years. “AI finance ministers and central bankers” might also distribute global resources more efficiently, helping sub-Saharan Africa boost economic growth rates by more than 10 per cent. Amodei even speculates that AI might improve societal governance and reinforce democratic institutions rather than erode them.

Accepting it is only possible to make “guesses” about the future, Amodei acknowledges that many readers might consider his essay “absurd fantasy”. Nevertheless, his thoughts are an enlightening glimpse into the future that leading AI executives imagine they are building. Given the astonishing pace of AI’s development, it would be rash to dismiss such futurism out of hand. We could certainly use an intoxicating shot of optimism in these bleak times.

Yet somehow these AI debates about a gleaming future remind me of the theoretical Marxist-Leninist dialectics I spent too much time studying at university. Early communists believed that vast, impersonal forces would inexorably reshape society almost irrespective of human input. It was pointless to resist the future, which would arrive whether we wanted it to or not. But, as we know, history did not unfold that way.

It would be unfair to suggest that Amodei — or his fellow AI champions — are as blindly doctrinaire. Indeed, they have expressly warned of the technology’s uncertainties and dangers. But they do seem to commit a similar teleological fallacy in assuming that humanity will flex to outside forces, in this case technology, rather than the other way around. In internet speak, they may need to get out of the office more to “touch grass” — or at least wait to see the outcome of the US election on November 5.

There is little doubt now that AI could immeasurably benefit humanity, but it cannot correct all human imperfections, nor should we even want it to. “Out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing was ever made,” the philosopher Immanuel Kant taught us. That lesson applies to all would-be humanity straighteners: whether they be Bolshevik revolutionaries or AI evangelists.

#compress #21st #century