France grapples with its budget mess

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Michel Barnier and his new minority centrist-conservative coalition were always going to face a formidable challenge governing France at a time of populism and polarisation. But their task has been made all the more difficult by the fiscal mess bequeathed by Emmanuel Macron and his ministers after seven years in power.

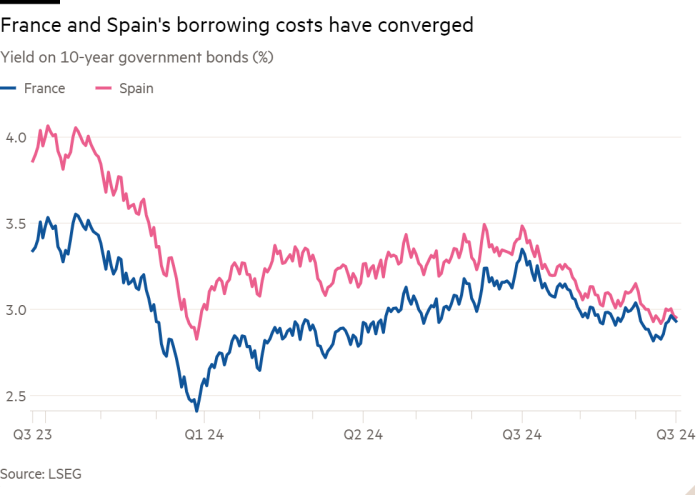

The last government lost control of the public finances. The public deficit is due to hit 6.1 per cent GDP this year, a massive slippage from the 4.4 per cent envisaged when the draft 2024 budget was first outlined 18 months ago. It is a significant miss that tarnishes Macron’s record. It has also unnerved financial markets with France’s 10-year bond yields converging with Spain’s.

After five decades without a balanced budget, France’s public debt now stands at 110.6 per cent of GDP. The French Council of Economic Analysis has argued that France can no longer rely on growth to automatically reduce its debt ratio. Given the deterioration in its fiscal position, France is now being forced into a painful fiscal adjustment to comply with EU fiscal rules, reassure investors, and protect the interests of its taxpayers who otherwise will have to pay for spiralling borrowing costs.

Earlier this month, Barnier unveiled a budget which he said aims to reduce the deficit to 5 per cent by the end of 2025. There would, he said, be €60bn worth of savings, with two-thirds of it from spending cuts and one-third from tax rises. The numbers are in some ways better, in other ways worse, than presented. On the plus side, the real adjustment is closer to €42bn, because Barnier based his €60bn on an improbably high trajectory of public spending growth. On the downside, as noted by the High Council for the Public Finances, the official budget watchdog, most of the savings actually come in the form of tax rises, notably on large companies’ profits and top earners.

In his defence, Barnier had little time to prepare the budget let alone the long-term public finance plan that France badly needs and the EU demands. His plan, while inevitably crimping growth, may do less damage to short-term demand than generalised tax increases or hasty spending cuts. The danger is that the additional levies on corporate profits and the wealthy will deter investment and damage the pro-business climate that was one of Macron’s biggest achievements. Supposedly temporarily, they risk becoming permanent.

To be fair, Macron has attempted cost-saving reforms such as raising the pension age. Still, he has not been serious enough. He had to contend with the pandemic and cost of living crisis, but his “whatever it costs” response was excessive and many measures were insufficiently targeted. Like his predecessors, he has also tended to use funds to defuse social tensions. Tax cuts for business and households were not matched with spending restraint.

With tax as a share of GDP at 46 per cent, the highest in the OECD, further revenue-raising will harm France’s competitiveness. Some costly tax breaks can be trimmed but spending cuts will have to take the strain, particularly on welfare and local government. The government might also consider whether its many corporate holdings still count as strategic when it needs to invest in innovation, decarbonisation and defence.

This crisis has been a long time in the making. France’s political class no longer seems to value fiscal discipline — as shown by the wild spending promises made by major parties during this summer’s elections. Barnier will get his budget through parliament, by decree if necessary. He lacks a majority and a mandate for long-term reform but if he can start to bring the country to its senses he will do it a great service.

#France #grapples #budget #mess