Peak population may be coming sooner than we think

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Every few years, the latest data from the UN’s World Population Prospects is hurriedly plugged into thousands of spreadsheets and models in banks and government finance ministries the world over, as investors and economists set out their plans for the years ahead.

The UN’s numbers are considered the gold standard, but Seattle-based public health research group the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation is also a big player. Vienna’s International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis also publishes respected projections every few years.

The methods vary. Some stick to demographic and economic inputs, while others make assumptions about social change. As a result, the outputs also differ. The UN’s latest central estimate forecasts that the global population will peak at 10.3bn in 2084. The IIASA puts the peak at 10.1bn in 2080, and IHME at 9.7bn in 2064.

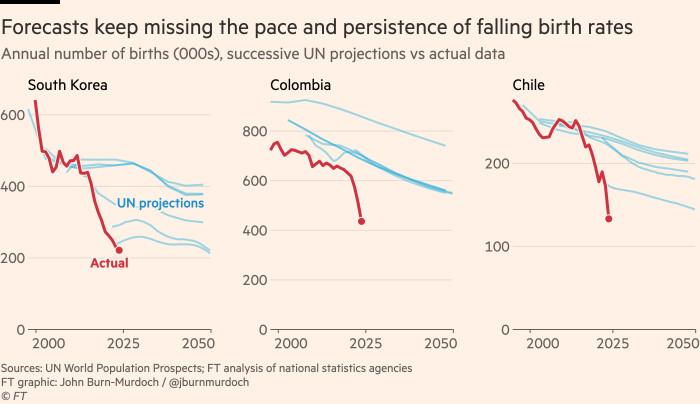

But, one after another, the projections keep missing, repeatedly underestimating the pace and duration of falls in birth rates. To give one example, just five years ago the UN estimated that there would be around 350,000 births in South Korea in 2023. There were actually 230,000, more than a third fewer.

South Korea is almost too lazy an example in demographic discourse, but similar misses are increasingly common. Jesús Fernández-Villaverde, professor of economics at the University of Pennsylvania and a prolific researcher on the intersection of economics and demography, highlights Latin America, where the official birth tallies in country after country are falling far short of forecasts.

Last year in Colombia there were 510,000 births, a 22 per cent decline over five years, and around 30 per cent lower than even the UN’s nowcast for that same year. From high-income Chile to emerging Guatemala it’s a similar story, and this issue is far from specific to the UN data, whose projections are generally closer than those of the IHME and IIASA.

Until recently, ultra-low and rapidly falling birth rates were primarily a concern for rich countries, especially those in east Asia. But many still-ascendant countries now have lower fertility rates than much wealthier ones. Last year, Mexico’s birth rate fell below that of the US for the first time.

According to Fernández-Villaverde’s calculations, the combined impact of the yawning misses for emerging market countries and smaller overestimates for wealthy western nations puts the true global population trajectory on the UN’s “low fertility” pathway. That would mean a peak at around 9bn in 2054, 30 years earlier than in the headline forecast.

To be fair, the UN’s forecasts of a tentative recovery in birth rates are not plucked out of thin air, but modelled based on the uptick in fertility experienced by dozens of wealthy countries in the 1990s and early 2000s. Looking back further still, parts of Europe had Korea-esque birth rates early in the 1930s that came bounding back after the second world war.

FT Edit

This article was featured in FT Edit, a daily selection of eight stories to inform, inspire and delight, free to read for 30 days. Explore FT Edit here ➼

But postwar rebounds and the mini-boom of the 1990s were characterised by healthy economic growth and broader societal optimism. It’s not clear we have those prevailing winds today. Similarly, the pace of decline in many middle-income countries’ birth rates suggests the link between economic development and family size plays out differently in different contexts.

For a while, it was thought that we would see a U-shaped trend: fertility falling with development, then rebounding. But new research found that theory was no longer borne out in the aggregate.

Back in South Korea, the total fertility rate in Seoul last year fell to just 0.55 births per woman. Clearly, ultra-low can become ultra-ultra-low. But just as steadfastly rosy forecasts of stabilising or rising birth rates look increasingly like the wrong framework, it would be equally foolish to simply extrapolate recent downward trends forward indefinitely. Korea’s birth rate this year is set to be roughly unchanged, and rates are rising across much of central Asia.

Projecting a dynamic system forward is incredibly challenging. Even tiny perturbations today can compound into yawning gulfs. At any rate, no sensible reading of the latest data supports the idea of “global population collapse”.

But perhaps the next edition of projections should come with a health warning: these estimates are extremely fuzzy and based on frameworks that were true in the past but may not be today. Use them with caution, and probably err on the low side.

[email protected], @jburnmurdoch

Data sources and methodology

Total fertility rate: “For a given year, the total fertility rate represents the average number of children that would be born to a hypothetical woman if she (1) lived to the end of her childbearing years, and (2) experienced the same age-specific fertility rates throughout her whole reproductive life as the age-specific fertility rates seen in that particular year.” — OurWorldinData.

Data for observed birth numbers and fertility rates (as opposed to the projected figures) are taken from individual countries’ vital statistics collections. In most cases these are annual figures ending with 2023, but some charts also show a nowcast 2024, which is calculated by comparing the number of births recorded so far in this calendar year with the same months in 2023, and applying the resulting rate of change to the annual figure for 2023. Adjustments are also made for changes in population age structure in the case of the TFR, based on prior work by @BirthGauge.

#Peak #population #coming #sooner