Does the EU have a strategy for gas?

This article is an on-site version of our Energy Source newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every Tuesday and Thursday. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

Good morning and welcome back to Energy Source, coming to you today from London.

In Europe, oil and gas earnings season has begun with UK-listed BP reporting its lowest quarterly profit since the Covid-19 pandemic as lower oil prices and weak refining margins weighed on its performance.

A 30 per cent year-on-year drop in earnings will maintain pressure on chief executive Murray Auchincloss who has pledged to make BP “simpler, more focused and higher value” but has so far struggled to boost performance, which has largely lagged behind rivals in 2024.

BP maintained its planned share buybacks for this year but signaled it would review its framework for shareholder returns for 2025. Analysts are forecasting an inevitable drop in the pace of buybacks next year given the weaker market environment.

While BP’s profits still beat estimates, the more downbeat market tone sets the scene for a potentially difficult week for the oil and gas majors, with earnings now far below the record levels set in 2022 and 2023. Shell and Total Energies report on Thursday and ExxonMobil and Chevron on Friday.

Today’s piece comes from Brussels where the FT’s EU correspondent Alice Hancock has been investigating how the bloc buys its gas. — Tom

EU gas ‘the sticky wicket’ holding up the energy transition, says US LNG producer

Does the EU have a strategy for gas?

That is the question posed by the one of the biggest liquefied natural gas producers in the US, which is keen to offer EU countries flexible contracts that will not lock them into long-term fossil fuel use.

The strategy for coal is obvious, William Jordan, chief legal and policy officer at EQT, has told Energy Source. “Get off coal. That’s easy.”

Then there is the wider planning for renewables — scaling up as fast as possible — and the beginning of a rethink on nuclear power.

But for gas, Jordan argued, there was no formal policy framework and no one really agreed on what referring to gas as a “transition fuel” meant.

“Natural gas is square in the middle. It’s the hardest of the sticky wicket. And it’s also not surprising that a failure to address that sticky wicket is what causes the problems in the entire [energy] transition to arise. We’re at the point where now’s the time that we can have this discussion. And I think it’s going to be very important that we do so in the near term.”

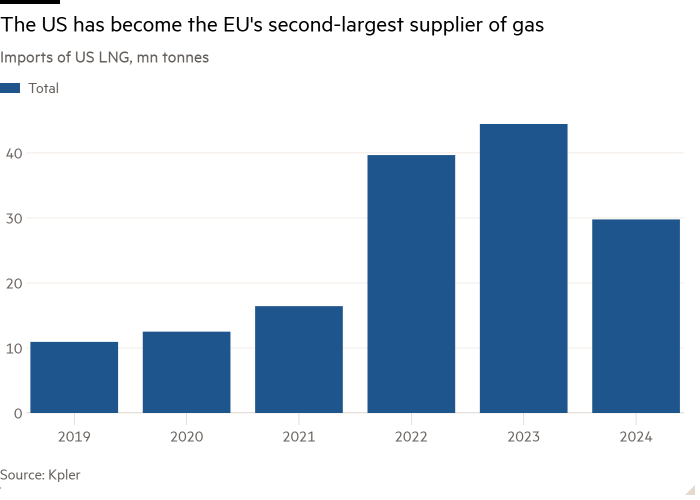

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the EU has become increasingly reliant on US LNG to replace volumes of Russian gas. Imports shot up from 16.4mn tonnes in 2021 to 39.7mn tonnes in 2022 before hitting a record 44.4mn tonnes last year, according to Kpler data.

That does not mean that Russian gas has been replaced. EU governments have recently warned that despite the precipitous fall in pipeline supplies from its eastern neighbour, shipments of gas into western ports in countries such as Belgium and France have crept up.

The major push from the EU has been to replace what is lost from Russian gas with renewable power. But the intermittency of renewables and infrastructure challenges means that gas looks set to retain a significant share of the bloc’s energy mix.

Jordan’s argument is for the US and EU to consolidate a transatlantic gas strategy that goes beyond their joint energy security task force established in 2022 to help the EU diversify its gas supplies, which has not officially met since October 2023.

US suppliers can offer EU buyers “an option-type contract, not requiring Europe to purchase, just giving it the option”, Jordan said, in contrast to Qatari peers who tend to demand longer-term lock-ins that would run counter to the bloc’s climate goals.

A study from the Centre on Regulation in Europe, a think-tank, suggests that such flexible contracts, which could also offer caps and floors on prices, could help reduce European wholesale gas prices by €343bn by 2030 by protecting consumers from volatile markets in times of high demand.

But the problem was that “it is not the role of the governments to sign contracts for LNG. This is something that belongs to companies,” said Simone Tagliapietra of the Brussels-based think-tank Bruegel.

“It is difficult to expect European governments to do more than they have been doing over the past years signing [memorandums of understanding],” he added.

In a landmark report on the EU’s competitiveness published last month, former Italian premier Mario Draghi recommended aggregating demand for gas and joint buying.

Amund Vik, former state secretary for energy in Norway, now the EU’s biggest gas supplier, said “it would be easier for Europe to get better or more flexible contracts if Europe was able to leverage its size”.

But efforts to start that have been underwhelming.

Among the multiple challenges are that energy mix is a national, not EU, responsibility and that EU governments are underestimating the need for gas long term — or at least until batteries are available at such a scale that they can compensate for intermittent renewable power.

“As long as Europe refuses to crystallise this long-term natural gas demand, it will be stuck with worse contracts,” Vik, now a senior adviser at Eurasia Group, said.

Vik predicted that whatever the policy machine did, geopolitics dictated that US producers would naturally focus on the EU in the short term.

“Despite the shenanigans going on with the current US election, it is still economically and politically much closer to Europe [than the Middle East is], so that is important and it is a somewhat secure trade route.”

Part of the reason for EQT’s pitch is the impending election on November 5. The more demand there is from Europe, the more reason the US producers have to pump and to lobby the government to ease up on what Jordan called “frivolous litigation”, including a freeze on approvals for new LNG exports from the US announced by President Joe Biden in January.

“If I’m the EU, I want to be making sure that the United States is doing what it can to reduce the costs that will ultimately be passed on to my consumers in the EU,” Jordan said.

But he should perhaps not hold his breath.

In answers drafted for the EU’s potential new energy commissioner Dan Jørgensen ahead of a parliamentary hearing next week, seen by Energy Source, the bloc’s energy directorate writes that US producers should not expect higher demand from buyers across the pond. “We will continue to import US LNG, but at lower volumes in the future as [the] EU’s overall gas demand decreases as part of the fossil fuel phase out.” (Alice Hancock)

Power Points

-

Data centres, often criticised for their intensive need for energy, could be a source of heat for European cities, according to the boss of one of Europe’s leading energy transition companies.

-

Oil prices fell sharply yesterday after Israel’s attack on Iran at the weekend avoided oil and nuclear facilities and Tehran gave a measured response to the strikes.

-

Hungary’s largest oil group has defended the country’s dependence on Russian energy, pointing to the “hypocrisy” among its western allies for buying “repackaged” fuels from Turkey or India.

Energy Source is written and edited by Jamie Smyth, Myles McCormick, Amanda Chu, Tom Wilson and Malcolm Moore, with support from the FT’s global team of reporters. Reach us at [email protected] and follow us on X at @FTEnergy. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.

Recommended newsletters for you

Moral Money — Our unmissable newsletter on socially responsible business, sustainable finance and more. Sign up here

The Climate Graphic: Explained — Understanding the most important climate data of the week. Sign up here

#strategy #gas