Billions in taxes hang in balance for US companies as election nears

In the race for the White House, the largest companies in the US are facing two starkly different financial futures, separated by one vast sum: a quarter trillion dollars a year.

The potential price tag is thanks to the differing tax policies of the two candidates, one of the most crucial distinctions between them for corporate America. Kamala Harris is promising to partly reverse Donald Trump’s big reduction in the corporate rate, while the former president says he will lower it further, intensifying a debate over the legacy of his 2017 reforms and setting the stage for a year of wrangling with the new Congress that will also be elected on November 5. Big business, meanwhile, is gearing up to protect its gains.

The quarter-trillion figure is based on estimates from Goldman Sachs, which says Trump’s proposal to cut the corporate rate from 21 per cent to 15 per cent would add 4 per cent to the earnings of the S&P 500. Harris’s plan to raise it to 28 per cent would reduce earnings by 5 per cent, the Wall Street bank estimated, and her other corporate tax proposals would shave a further 3 per cent.

On S&P 500 earnings that are forecast to be $2.2tn next year, the 12 per cent difference between the impact of the candidates’ policies explains why executives are paying attention — and illustrates why the Business Roundtable has earmarked “eight figures” to campaign on tax issues over the next year, one of the largest such efforts in the lobby group’s 52-year history.

“If Republicans sweep, you get one set of results,” said Rohit Kumar, who co-leads PwC’s national tax practice, advising corporate clients on the possible outcomes. “Democrats sweep, you get a different set of results. Divide the government and you get something somewhere in the middle. There’s no way to describe this other than that this is a significant fiscal event.”

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act signed into law by Trump in December 2017 was the most sweeping reform of the US tax system in a generation, cutting rates for individuals and revamping how US corporations are taxed. From having the highest corporate tax rate in the OECD, at 35 per cent, the law at a stroke brought the US into line with the average of the group of developed nations. It also largely stopped taxing US companies on profits they make overseas and repatriate to the US, and contained other incentives including bigger than usual tax deductions for some investment spending.

The law offset more than half the giveaway by limiting corporate deductions such as for interest expenses and some of the investment incentives were scheduled to expire or become less generous over time. But the overall result was a swift and enduring windfall for the US’s biggest companies in recent years that now likely surpasses $1tn.

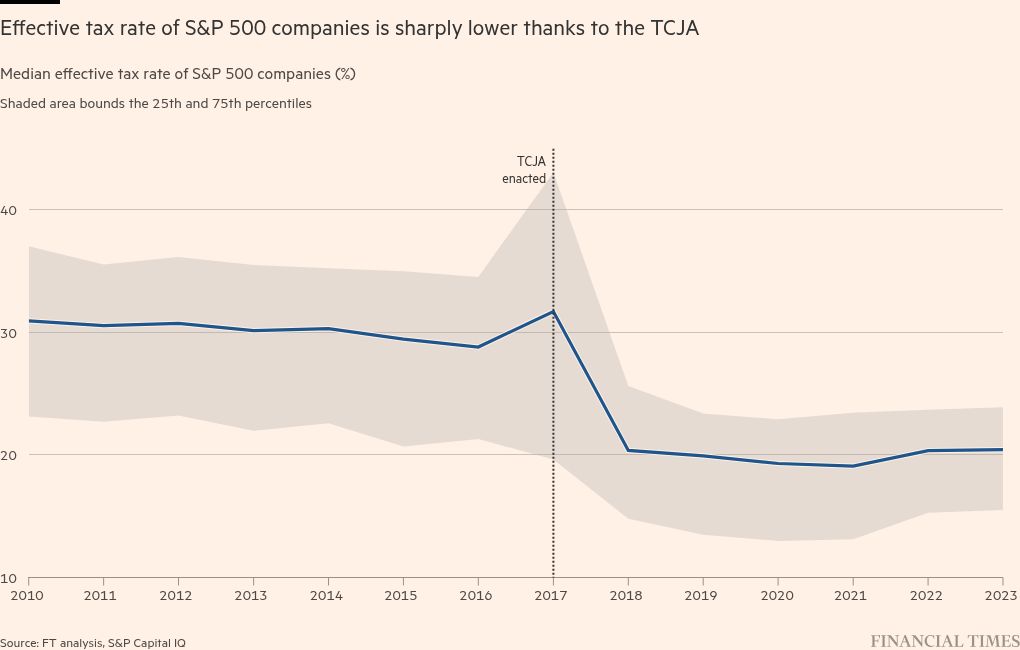

A Financial Times analysis of S&P Capital IQ data shows the median S&P 500 company had an effective tax rate of 20 per cent last year, compared to 28 per cent in 2016. In the six years from 2018 to 2023, S&P 500 companies provisioned a total of $1.8tn for taxes globally, or about 18 per cent of earnings before tax. If the pre-TCJA average of 27 per cent had persisted, the tax bill for those six years would have been $932bn higher, according to the analysis.

Harris has attacked the TCJA on the campaign trail as a giveaway to billionaires and corporations, and Democrats have cited evidence from academic studies that it failed to live up to claims it would significantly increase wages and benefits for workers.

The extent to which the law raised corporate investment in the US also remains controversial. An early knock on the reforms was they led not to investment but to a spike in share buybacks, which jumped above $800bn across the S&P 500 for the first time in 2018 and have stayed elevated since.

Companies including Apple and Microsoft noted they could now repatriate profits made overseas for distribution to US shareholders without penalty, whereas before they might take on debt, with associated interest costs, to fund buybacks.

The Business Roundtable’s vice-president for tax and fiscal policy, Catherine Schultz, has cited the strength of the US economy in the two years before Covid-19 hit, including unemployment at 50-year lows, as evidence of the reforms’ “immediate and profound” effect.

Chief executives of companies from General Motors and AT&T to Qualcomm and Amazon have said the TCJA factored into decisions to build new factories or make other long-term investments in the US.

Earlier this month, Johnson & Johnson’s chief financial officer Joseph Wolk, cited the “fair rate” of 21 per cent as a factor in siting a new drug supply facility in North Carolina, and he told CNBC that plans for a more advanced cell and gene therapy facility could be dependent on the rate staying there. “If the rate goes to 28 per cent, I think it’s going to be very difficult to put that facility in the US,” he said.

According to the FT’s analysis of S&P Capital IQ data, research and development has risen as a proportion of revenues among the S&P 500 to 3.7 per cent in 2023, continuing a trend that predates the TCJA, while capital expenditure has remained steady. Both figures reflect investments companies made globally.

It is not simple to untangle the impact of the TCJA on investment in the US from subsequent developments such as the post-Covid rethink of supply chains and the massive subsidies for green and tech investments unleashed by the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act and Chips Act, or from what has been a generally buoyant economy.

Economic modelling by bipartisan or independent experts has found the TCJA did lead to expanded capital investment in the US — by 20 per cent, according to one model — and a study from a team of academics led by Javier Garcia-Bernardo of Utrecht University identified Alphabet, Microsoft, Qualcomm, Meta, Nike and Cisco as companies that moved intellectual property back to the US in the wake of the TCJA.

PwC’s Kumar said: “Before 2017, if a taxpayer was looking for a home for its intellectual property, the US was not really in the conversation. Post-TCJA, it was very much in the conversation. Overall, the TCJA made the US a much more competitive place and you saw, in my observed experience in talking to taxpayers, a marked shift towards the US market from an investment thesis perspective.”

There is less agreement on which aspects of the TCJA had the biggest effect, the headline rate cut or more targeted provisions such as bigger than usual tax deductions for the cost of some investments.

“The economic bang for the fiscal buck varies across different tax provisions,” Harvard professor Gabriel Chodorow-Reich wrote in the most recent Journal of Economic Perspectives, calling the headline rate cut “a blunt instrument”. “It matters whether corporate tax reform encourages new capital via investment incentives, rather than by enriching old capital via corporate income tax rate cuts.”

Corporate America is pushing for Congress to revisit the TCJA as soon as possible. Some of the targeted investment incentives in the act have begun to phase out, and the law made the treatment of R&D spending less advantageous from 2022. Provisions related to foreign income are also set to become less generous for US multinationals next year. The headline rate cut, however, was “permanent”, meaning it will stay at 21 per cent if Congress does nothing.

Most observers expect lawmakers will revisit tax rates in 2025 because the cuts in personal tax rates that were in the TCJA will expire if they do not, with potentially damaging political consequences. Predicting the outcome, however, is fraught, given the jumble of interlocking provisions, and the competing priorities outlined by Trump as he has mused about axing taxes on tips, overtime and Social Security benefits among other sources of income for the federal government.

EY tax adviser Adam Francis, on a webcast for clients this month, said the complexity of the TCJA will complicate negotiations, regardless of the political make-up of Congress. “And complication opens the door to risk,” he said.

“Investors should absolutely be watching this,” said Monica Guerra, head of US policy at Morgan Stanley Wealth Management, who predicted a “Trump rally” or a “more modest Harris correction” in the stock market depending on which candidate prevails next week.

“It is critical and the policies are vastly different, but rather than who is president, we are focused on what happens in Congressional elections, because that will be important to how the sausage is made.”

PwC’s Kumar said companies are holding off on major investments, because the outcome on November 5 will have such significant implications for tax rates. It is only after the results are clear that they will be able to calculate how it will affect them.

“Large companies that are making big dollar investments are doing math,” he said. “They’re investing on the math, not on the vibes.”

#Billions #taxes #hang #balance #companies #election #nears