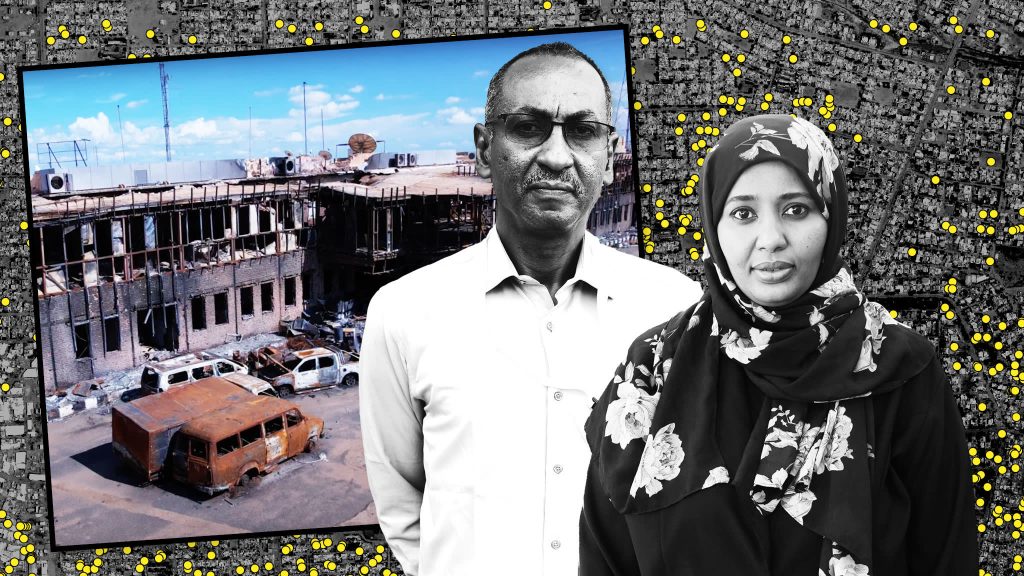

Fierce fighting has gripped Sudan. Hospitals are in the firing line

Al-Nou was struck at least three times, the last in June, and staff have also been directly attacked by armed men.

More than a dozen doctors have been abducted by RSF militiamen and some taken across the frontline of the Nile. The RSF — led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, a feared warlord and former camel trader known as Hemeti — are said to have taken much of the capital region and need doctors to treat their own men.

According to health authorities, 54 doctors have been killed in Khartoum state since the war began, some of them by snipers. About 70 to 80 per cent of Sudan’s healthcare facilities are not operating at full capacity.

Deliberate targeting of healthcare constitutes one of the gravest violations condemned by the UN Security Council. The Rome statute, which established the International Criminal Court in The Hague, includes on its list of war crimes “intentionally directing attacks” against “hospitals and places where the sick and wounded are collected”.

Yet doctors and officials say these attacks are no accidents. “From the first day of the war [RSF forces] were specifically targeting the health sector,” said Mohamed Ibrahim, head of the emergency health committee of Khartoum State.

He said that before the war, when the state had a population of more than 9mn people, there were 53 public hospitals operating; now there are only 27. The RSF’s “main purpose is to destroy the health sector; if you destroy the health sector and then the security sector, the country collapses”.

Dorsa Nazemi Salman, head of operations in Sudan for the International Committee of the Red Cross, said that “shelling and looting of hospitals led to the near collapse of healthcare”.

“Under international humanitarian law, healthcare facilities and medical personnel are specifically protected against attacks and other military interference with their functioning, and they must not be targeted,” she adds.

RSF officials acknowledge some of its troops — who have also been accused of rapes, killings, lootings and ethnic cleansing — have “committed crimes”, but claim that the force has established a committee to investigate abuses and hundreds have already been punished.

Yet the attacks have not stopped. Maha Hussein, director of Al-Bolouk children’s hospital in Omdurman, shows the marks of a rocket that pierced a wall, blowing up the laboratory in July — the third attack since the war started. “The hospital is attacked all the time, it’s a disaster,” she said.

At Bashair hospital in south Khartoum, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) said there were “recurring security incidents and intimidation in the wards by armed RSF combatants”.

Burhan and Hemeti had once been on the same side, the two military leaders joining forces following a popular uprising against the country’s longtime strongman, Omar al-Bashir, that led to the former leader’s ejection in 2019.

But their brutal fallout has split Sudan into two warring camps, and caused the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. More than 11mn people have been forced to flee their homes and over half of the population is on the verge of famine.

The fighting, which has affected most regions, has been heaviest in Khartoum, North Darfur and Al-Jazirah states. According to conflict monitoring group Acled, RSF violence against civilians reached its highest level since the war began in the first half of 2024.

#Fierce #fighting #gripped #Sudan #Hospitals #firing #line