Mixed news on China’s stimulus

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every weekday. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

Good morning. A question for readers: will we see a significant shift in consumer sentiment now that a change in presidential administrations is coming? As a reminder, the University of Michigan sentiment index, at 70, is 40 per cent off of its 2022 lows, but still well below historical averages. Will there be a step change in the next survey or two, or a continuation of the current trend? Send us your thoughts: [email protected] and [email protected].

Chinese stimulus

Holders of Chinese equities got mixed news on Friday. At the National Peoples’ Congress meeting, the government announced an Rmb10tn ($1.4tn) fiscal package to bail out local governments’ bad debts. The package itself, following the pattern of recent stimulus measures, is underwhelming. The Shanghai and Shenzhen CSI 300 stock index and the Rmb edged down on the news:

Bad debt is a problem for China. Chinese local governments, which are not able to issue their own bonds, have traditionally used financing vehicles similar to investment companies to borrow money; after the real estate market crash, many provinces could no longer use land sales to pay back those loans, resulting in bad “hidden” debt not on their official balance sheets. Swapping out the debt will limit financial risks and free up spending capacity, at a moment when many local governments have cut back on public services. But the size of the relief is relatively small. From Tianlei Huang at the Peterson Institute:

The impact of this package on the immediate economic situation will be limited. [Finance minister Lan Fo’an] estimates that local governments will save about Rmb600B [$83bn] in interest payments over five years. [Rmb120B, or $17bn] each year is just too small to make a difference . . . the actual spending [by the local governments] so far this year is almost Rmb3tn [$417bn] lower than the amount that was budgeted [for] this year.

Rmb10tn is probably not enough to make a lasting dent in the hidden debt problem. While Lan said there is around Rmb14.3tn ($2tn) in hidden debt on provinces’ balance sheets, the IMF put the number at Rmb60tn in a report last year. On top of that, the Rmb10tn number is not all new commitments. While Rmb6tn of new debt will be issued for the debt swap facility, Rmb4tn is debt that was already available to local governments for related purposes.

Without more muscular stimulus, chances that the economy will hit the government’s 5 per cent growth target this year remain low. But more may be forthcoming. The MOF meeting in October laid out four goals of the stimulus, of which resolving local hidden debt was the first (followed by boosting bank lending, stabilising the real estate market, and supporting consumers). While we are not sure they will continue to be rolled out in the announced order, statements made by Lan imply the government will deliver on the other three goals.

Markets have been impatient for details on the stimulus. The timing of this package, right after the US election, suggests that the Chinese government was waiting to learn who would win the White House before making strong financial commitments. And the scale of this package raises the possibility that the government is saving its fiscal firepower in order to respond to the Trump administration’s eventual China policies. A more concrete and substantial fiscal package may emerge soon.

(Reiter)

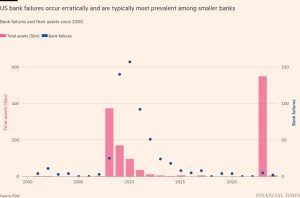

Regional banks

Regional banks rallied furiously after Donald Trump was elected. The KBW Regional Bank Index, which has been a terrible performer for years, is 12 per cent higher than the day before the election. Does this make sense?

The reasons to be bullish on banks under the new administration are something of a grab-bag. Lighter regulation should help a bit, though Basel “endgame” capital rules have already been watered down. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s cap on late credit card fees, currently in legal limbo, seems likely to disappear now, which will help issuing banks. And it appears that bank investors never believed Trump’s own promise to cap interest rates on cards at “around 10 per cent.”

Lighter touch regulation of mergers will certainly help big banks with merger advisory operations. But it could help the regionals, too. Consolidation among midsized banks makes economic sense in an industry dominated by a few large players. But it is not clear — at least to Unhedged — that merger rules were the most important bottleneck to consolidation. The problem, instead, has been getting the management teams of acquisition targets to give up their prestigious, well-paid jobs. This is what made the 2019 merger of BT&T and SunTrust, creating Truist, so remarkable.

More important is Trump’s impact on interest rates. If you believe that Trump means high deficits, low taxes, and high growth, all that suggests that the Fed will keep short term interest rates relatively high. And high — but not too high — short term rates are good for banks. Here is a chart of the US banking industry’s net interest income plotted against the policy rate:

The magnitude of the changes in net interest margins is much lower than the magnitude of changes in the Fed policy rate. But remember that very small shifts in net margins make big differences in banks’ net income. And while many banks have sources of revenue that are not rate sensitive, for regional banks, interest margins are important.

At the same time, the old cliché that banks borrow short and lend long still persists. This would suggest that bank margins are better when the yield curve is steep. To the degree that a given bank has a significant amount of long-term bond or mortgage assets on its balance sheet, this may be true. But in the last five years, the relationship in the industry has been almost the opposite of what the cliché would suggest (note that this chart is quarterly, so it does not capture the recent steepening of the yield curve):

But here is the weird thing: financial reality and market perception are different. One bank analyst of long experience noted to us that while the yield curve is not particularly important for regional bank profits, buying regional banks when the curve steepens is a “turn off your brain trade”. Whether it matters for earnings or not, bank stocks rise on a steepening curve. Here is the KBW regional bank index and the Treasury curve:

The relationship is sloppy in detail, but it is clear that big moves in the curve move bank stocks.

So a key question for regional bank stocks is whether the curve will continue to steepen; if it doesn’t, the nascent rally may stall. Many economists have argued that Trump’s policies are, on balance, inflationary. If that’s right, and the Fed has to lean policy against them, the curve may stay flat. But Trump, and his policies, have been known to surprise people.

One Good Read

On polling.

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.

Recommended newsletters for you

Due Diligence — Top stories from the world of corporate finance. Sign up here

Chris Giles on Central Banks — Vital news and views on what central banks are thinking, inflation, interest rates and money. Sign up here

#Mixed #news #Chinas #stimulus