World Without End — the hit graphic novel making the case for nuclear power

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In 1982, a British graphic novel called When the Wind Blows by Raymond Briggs conjured the cold war nightmare of nuclear annihilation so powerfully it became a bestseller that spawned a stage play, a film and a radio play.

Four decades on, bestseller shelves have filled with another graphic novel about another existential dilemma, climate change, that suggests salvation lies in, yes, nuclear power.

It is probably no accident that World Without End is written by two Frenchmen, energy and climate consultant, Jean-Marc Jancovici, and comic book artist, Christophe Blain.

France may be better known for the Eiffel Tower and Brie. But it is also a nuclear powerhouse with a huge fleet of reactors that last year got a whopping 64 per cent of its electricity from splitting atoms. But we are getting ahead of ourselves, or rather, ahead of the way Jancovici and Blain want us to think about nuclear power and global warming.

Their book joins the league of other big idea bestsellers that have either been transformed into graphic novels (Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens) or began life that way (Art Spiegelman’s Maus; Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis). Its colour illustrations are delightful. Its translation into English by Edward Gauvin from the original French is deft and witty. But readers expecting a narrative as compelling as Persepolis, or for that matter When the Wind Blows, are likely to be disappointed. Still, if statistics about energy use and climate science thrill, this is the book for you, though very young readers might struggle.

First published in 2021, World Without End begins as a disarming tale about Blain’s bumbling pleas for Jancovici to help him understand the best way to tackle the gathering climate crisis.

“Really?!” the Blain character gasps at intervals, as an all-knowing Jancovici tells of things like “Armor Man”, a superhero who can lift heavy things, fly super fast and never get too cold or hot in the process.

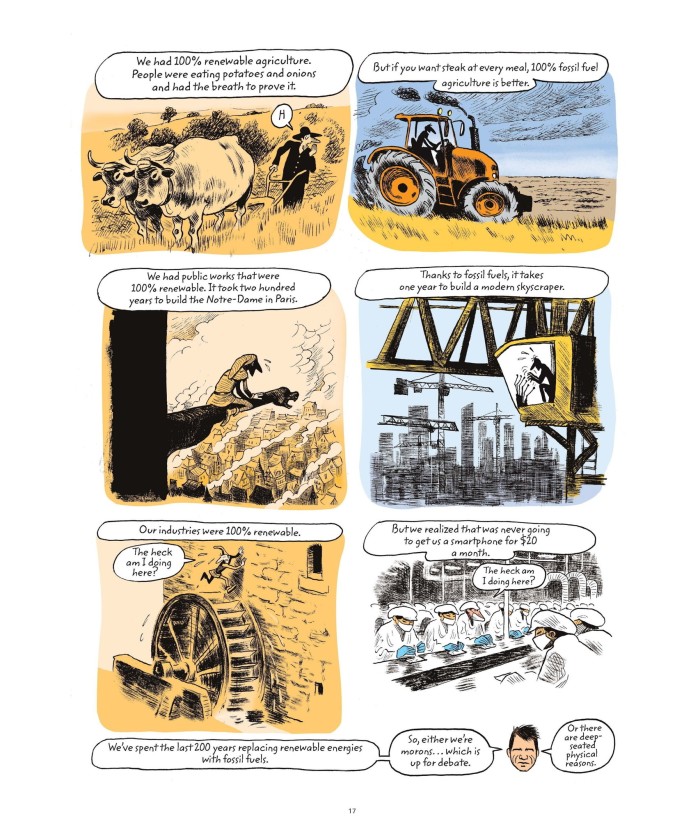

Armor Man feeds on “magical energy” that has transformed our daily lives yet costs less than 5 per cent of global GDP. This is of course fossil fuels, the coal, oil and gas that, along with the metals we mine, have created the cars, planes, plastics and machines that underpin today’s economies.

The first part of the book explains our addiction to these fuels and their impact. We’re told the number and size of dwellings has been able to increase faster than the population itself, which has in turn made it easier to divorce, which has led to twice the housing, appliances and furniture we once had.

But when the story shifts to the environmental costs of fossil fuels, things take a surprising turn as Jancovici declares “there is no green energy”. “All energy becomes dirty if you use it on a large scale,” he tells a forlorn Blain figure standing in a vast field of solar panels stretching to the horizon.

The price of a kilowatt-hour of power from a diffuse, low density source like wind, he adds, is about 100 times more expensive compared with that of a Saudi oil well. “And you still need oil, coal and gas to manufacture the wind turbine.” This may be true of today’s turbines, but leaders of the emerging green steel and green cement industries would rightly question how long it will remain the case.

The book’s message for renewables, battery storage and other alternatives to fossil fuels is also bleak. “Wind and solar have a nice image,” we’re told. But they require huge amounts of space and materials to produce decent amounts of power. Batteries “require more metallurgy and chemistry”.

Nuclear power plants may not be the whole answer, Jancovici says, but their defects are wildly exaggerated. About 30 people died shortly after the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, not the hundreds people imagine. About 6,000 people who were children at the time of the accident developed throat cancer. But “luckily, this is a form of cancer that can be treated effectively”. As for nuclear waste, most of it is shortlived. “The authorities pander to an inordinate fear of nuclear power rooted in a lack of understanding,” says Jancovici.

One waits in vain to read of the delays and costs afflicting new nuclear plants in places like the UK, where a boss at France’s EDF utility once said its Hinkley Point C reactor would be powering British homes by 2017. This year, EDF pushed back the project’s start date to 2029 at the earliest, at a cost many billions higher than the initial budget.

Jancovici is of course right to say all types of energy have flaws and “you have to pick your drawbacks”. But his concluding message to Blain is confusing and unsatisfying. “We know the old system won’t work for much longer,” he says, after an odd deviation into parts of the human brain that fuel our planet-wrecking predilections. “We must believe and take steps toward things that have a chance of coming true.”

As solutions to intractable problems go, this may not be the worst advice. But for a bestseller about the great challenge of our generation, one expects a little more.

World Without End by Jean-Marc Jancovici and Christophe Blain, translated by Edward Gauvin Particular Books £25, 196 pages

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen

#World #hit #graphic #making #case #nuclear #power