Tariffs are hard work

Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what the 2024 US election means for Washington and the world

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every weekday. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

Good morning. It is a pleasant irony that Bitcoin, the “anti-fiat” currency, has notched its highest value based on the outcomes of a US election, a decidedly governmental process. With the currency bouncing on political news, and crypto bros now clamouring to influence US politics, is crypto becoming — in its own way — more fiat than fiat?

Unhedged will be off tomorrow, and back in your inboxes on Thursday. Email us: [email protected] and [email protected].

Tariffs

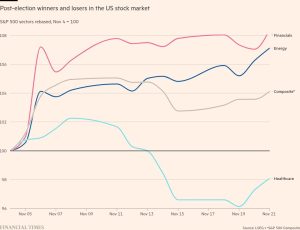

Trump is a tariff guy. He spent all three of his presidential runs lamenting the unfair treatment of the US in international trade, and put in place tariffs on China and US allies alike while in the White House. In this campaign cycle, he has publicly suggested blanket tariffs of 10 per cent to 20 per cent on all foreign trade, and expressed a desire to turn up the pressure on China by raising duties on all of its goods to 60 per cent. But, as we noted the other day, there is a lot of uncertainty around what his administration will do.

More China tariffs are surely coming. An enduring legacy of the first Trump administration is shifting the US’s policy consensus on Beijing. Joe Biden’s administration kept Trump’s China tariffs in place, and even added to them for electric vehicles and semiconductors, with bipartisan support. There is therefore little reason to believe Trump will back down from raising the pressure on the country further. Some have suggested his tariff pronouncements are part of a strategy to negotiate lower trade barriers for US goods, but this does not appear to be the case for China. Peter Navarro, Trump’s former economic adviser and a potential pick for Trump’s cabinet, wrote in Project 2025 that the president-elect feels “further negotiations [with China] would indeed be both fruitless and dangerous”.

Uniform tariffs present a larger unknown. It is possible Trump may try to place a 10 per cent rate across the board and call it a day; raising the US’s trade wall may be an end in itself to Trump. But reading into statements from Navarro and Robert Lighthizer, who Trump recently asked to take his old job as US Trade Representative, it seems more likely that universal tariffs will be part of a negotiating tactic. That is where things get tricky.

If negotiations are the goal, one possibility is the US does not actually raise tariffs to 10 per cent or 20 per cent at the outset, but instead raises them to match other countries’ own trade barriers, with the goal of getting those nations to lower their tariffs to the US rate. Lighthizer and Navarro support this approach, and Trump has already attempted it. His first administration tried to pass the US Reciprocal Trade Act back in 2019, which would have allowed the president to circumvent Congress and raise tariffs on any country with higher trade duties than the US.

If that is the case, we do not know whether the US will match other countries’ applied tariffs, the rate they actually apply to goods from the US, or their bound tariffs, the maximum they are allowed to place on a given class of US goods according to WTO rules. It would seem to make sense to go off the applied rate because that is what actually affects US producers — in essence, “whatever you do to us, we do to you”. This might have unintended consequences, however. From William Reinsch at the Center for Strategic and International Studies:

For example, Colombia may have a high tariff on coffee because they want to protect their coffee growers. Under Lighthizer and Navarro’s proposal, our tariff on coffee from Colombia would be ridiculous. We don’t grow any coffee. Our interest is to have zero tariffs on coffee. What [they are] talking about would lead you in the direction of having to reciprocate even if it is not in your interest.

If we go to the applied rate, the other country might go tit-for-tat, all the way up to their bound. So the US might choose to skip a step, and go straight to the other country’s bound rate. But, of course, that invites its own logical question: if we are not abiding by WTO laws, what is to stop other countries from going above their bound? The reciprocal approach relies on the idea that other countries care more about access to the US market than they care about protecting their own. This will vary by country and by product.

Which leads to the next point: a universal tariff would be cumbersome. US trade is shaped by tariffs on more than 6,000 products made by over 200 countries, regional associations, and territories. If countries do not immediately acquiesce to lowering their trade barriers, would Trump and Congress really renegotiate each item, line by line, with each trade partner?

There is little legal precedent for universal tariffs, too. The International Emergency Economic Powers Act, the broadest trade authority given to presidents, and Sections 232 and 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, which Trump used to impose trade levies in his first term, have not been used in recent history for across-the-board tariffs. Using any would probably lead to legal battles. And there is also no guarantee Congress will grant the president this authority through the Reciprocal Trade Act; even if Republicans win the House, Republican representatives will probably face pushback from exporting businesses in their districts.

In short, universal tariffs are hard work, and they are likely more disruptive than bilateral tariffs on China. Unhedged would be hard pressed to find a US company that will not be affected by such a levy. Nearly every company has some part of their supply chain outside the US. The Trump administration may successfully use the policy to negotiate away trade barriers on US products. But if universal tariffs are passed, and if other countries do not immediately give in to US demands, every sector with a physical input — hardware for tech, rebar for construction and real estate, or plastics for consumer goods — has the potential to be negatively impacted. As Alan Wolff, former deputy director of the WTO, put it to Unhedged: “We are in that time of life in international trade where strange incredulity is maybe the order of the day.”

(Reiter)

One Good Read

Energy myths.

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.

Recommended newsletters for you

Due Diligence — Top stories from the world of corporate finance. Sign up here

Chris Giles on Central Banks — Vital news and views on what central banks are thinking, inflation, interest rates and money. Sign up here

#Tariffs #hard #work