How will the Fed handle Trump?

This article is an on-site version of our Chris Giles on Central Banks newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every Tuesday. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

Two days after the US election last week, the Federal Reserve cut interest rates by a quarter of a point to a range of 4.5 to 4.75 per cent. That was expected.

Much more of a surprise was the aggressive tone Fed chair Jay Powell took to questions on his future under a Trump administration.

Reporter: Some of the president-elect’s advisers have suggested that you should resign. If he asked you to leave, would you go?

Powell: No.

Reporter: Can you follow up — do you think that legally that you’re not required to leave?

Powell: No.

Powell could have said he would not answer a hypothetical question, but chose not to. He later clarified that his terse answers reflected the reality, in his view, that a president firing a Fed chair was “not permitted under the law”.

Trump will be able to appoint the next central bank chair of his choosing when Powell’s term ends in May 2026. The nomination will need to be confirmed by the Senate, but the Republicans will have a healthy majority so that should not prove to be a barrier.

Sooner than that, however, the key moment is likely to be the nomination of a replacement on the Fed’s board of governors for Adriana Kugler, whose term ends in January 2026, as the table below shows. Other than that, the vast majority of Fed governors’ terms last beyond Trump’s presidency.

Earlier this year, I heard a cunning plan from Fed officials if Trump nominated someone who would put the US economy in danger as Fed chair. Colby Smith in the FT and the Wall Street Journal have now reported this and it is, in my view, a bad idea.

The plan is that if the next Fed chair was unacceptable to the Federal Open Market Committee, the rest of the FOMC would elect its own chair of the committee. That would neuter the chair of the board and maintain a FOMC leader who was able to keep monetary policy on an even keel.

This would be quite the nuclear option and would put unelected officials in a difficult spot, seeming to scheme behind the president’s back. The Fed might also want to update the Q&A section of its website which says categorically: “The Board chair serves as the Chair of the FOMC.”

If Trump’s pick was so dangerous, there would be a much less contentious way of proceeding. Just outvote the new FOMC chair’s bad policy suggestions.

For what it is worth, I expect this is all unnecessary bravado from the Fed. Much more likely will be that central bank intrigue under Trump plays out rather like the recent turmoil at the Banco Central do Brasil (BCB), which I wrote about a month ago.

This tale suggests that Trump will create much drama and unhappiness within the Fed by criticising its actions incessantly. He will then pick someone who is acceptable to the rest of the bank and when that person becomes chair, peace and harmony will break out.

Calibrating Trump II

Last week I described the struggle of economists trying to model Trump’s policies. These are ill-defined: before the election, economists did not know if he would have the power to implement them; and economic models are bad at predicting the effects of large structural shifts. Financial markets were not much better, I also argued.

One thing is clearer now. Trump’s Republicans will have a majority in the Senate and are likely also to have control of the House of Representatives.

The rest remains unclear for now, although Trump asking the protectionist Robert Lighthizer to be his trade representative suggests a real threat of extensive new tariffs.

Powell acknowledged these difficulties in his press conference after the FOMC meeting. “There’s nothing to model right now — it’s such an early stage,” he said, adding, “we don’t guess, we don’t speculate and we don’t assume”.

Of course, Powell had little choice but to say this. But it does put the Fed immediately behind the curve if Trump imposes significant tariffs right after his inauguration.

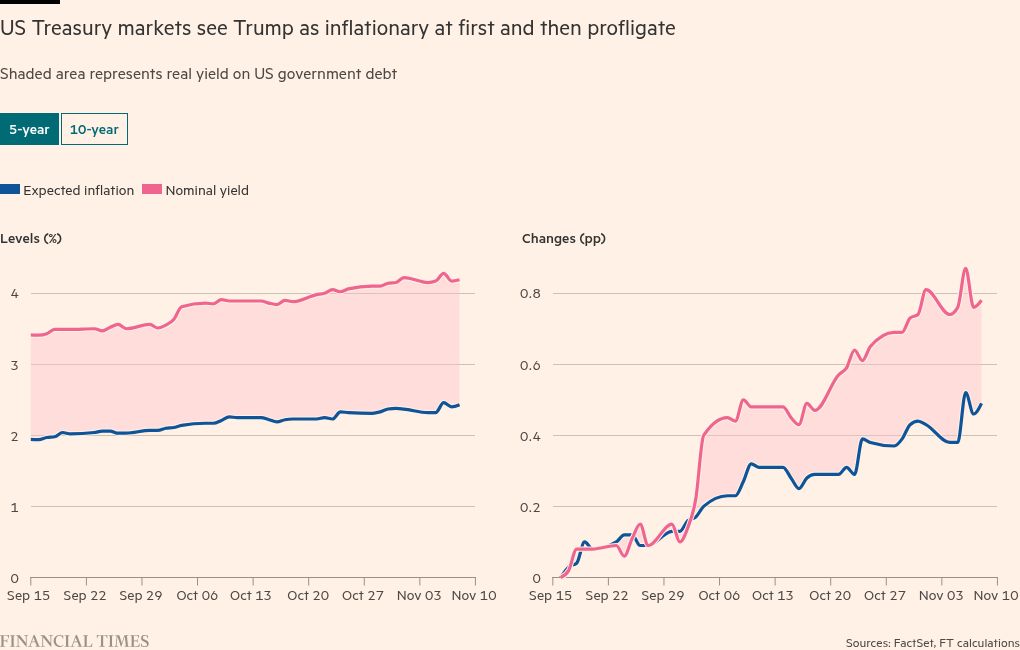

Financial markets are not finding it much easier to calibrate the likely Trump policy effect. The chart below shows US Treasury yields since September when they began to rise, split into the real rate of interest and an expected inflation rate component. I’ve also highlighted the change in these measures since mid-September. If you click on the chart, you can see the difference between market thinking at the five-year horizon and the 10-year horizon.

At the five-year horizon, more of the increase in nominal yields mostly reflects higher expected inflation, while the reverse is true at the 10-year horizon, where it reflects higher real yields.

This pattern is consistent with financial markets expecting tariffs to raise the price level, but ultimately not cause an inflationary problem. Inflation is implicitly contained between the fifth and 10th year. More profligate fiscal policy raises the real yield on Treasury debt in both scenarios.

Do not expect this view to last, however. Treasury markets have been volatile, so — like journalism — it is just the first draft of history.

In the SOFR (Secured Overnight Financing Rate) futures market, which provides a relatively clean market expectation of Fed funds interest rates, the increasing likelihood of Trump winning in the run-up to the election moderated expectations of rate cuts in 2024 and 2025.

Markets still expect a December rate cut, bringing the total number of quarter-point cuts this year to four, as the chart below shows. For 2025, financial markets now expect only a little over two quarter-point cuts now, down from five as recently as September.

What is most telling in these charts is not the Trump trade as far as we can interpret it, but the sheer variability of market interest rate expectations at all times. We should not over-interpret the past few months of movements as suggesting that financial markets have a clear idea of economic policy under Trump.

As Powell said, “It’s such an early stage”.

BoE forecasting revolution

In the UK, after the Bank of England reduced rates by a quarter point to 4.75 per cent last Thursday, governor Andrew Bailey sought to be as boring as possible about Trump. He largely succeeded, saying the BoE always responds only to “announced policies” and that it would work constructively with any US administration.

Much more interesting were the BoE’s forecasts. Remember the bank’s convention is to produce forecasts based on “market path” interest rates and “constant” interest rates, this time at 4.75 per cent.

The BoE has felt that going towards a model more like the Fed’s practice of deciding an “appropriate interest rate path” that would ensure price stability was so “consequential” that officials pressured Ben Bernanke not to put the recommendation in his review this year. (Although he clearly thought it was a good idea.)

BoE officials took the market path to be the average path in the 15 days before October 29, the day before the Budget, and that is represented by the pink line in the chart below. This had UK interest rates gradually falling to 3.7 per cent next year and the forecasts show inflation declining to 2.2 per cent in two years’ time and 1.8 per cent in three years’ time.

This is broadly consistent with the BoE’s inflation target, especially as those inflation forecasts include a highly implausible large assumed increase in fuel duties in April 2026.

Since October 29, however, the actual market rate path — the green line — has subsequently moved much higher to expect interest rates between 4 and 4.25 per cent by the end of 2025.

Without intending to, therefore, the BoE has just held a natural policy experiment of producing its forecasts on neither the market path nor constant rates, but what appears rather like an “appropriate path” necessary for stabilising inflation at the 2 per cent target.

As far as I can see, the sky has not fallen in.

Of course, the MPC did not have an opportunity to squabble about what the appropriate path should be, but it does suggest that some sort of appropriate rate path, perhaps selected by the staff, is a reasonable way forward. It would certainly help with communication.

What I’ve been reading and watching

-

Central banks face a bunch of bear traps with Donald Trump’s victory, I argued in a column

-

The former head of Spain’s central bank, Pablo Hernández de Cos, has been lined up as the next general manager of the Bank for International Settlements. He will replace Agustín Carstens next year

-

Sam Lowe tries to answer the big question in FT Alphaville. How, he asks, should you try to survive a trade war with the US?

-

Can you fight inflation and a war at the same time? Russia is finding it difficult

-

Trade Secrets writer Alan Beattie will hold a Q&A on Trump’s trade policy on Thursday. This is essential viewing

A chart that matters

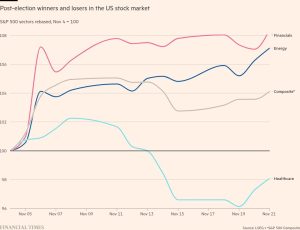

The US democratic party and pundits are already tearing themselves apart, with different accounts of Kamala Harris’s defeat.

I might be simple, but I don’t think the big picture is that difficult. You need to separate two things. First, Trump has always been popular as a presidential candidate, narrowly losing the popular vote twice and narrowly winning it once. This is persistent and I do not have much expertise in explaining why.

Second, there was a pretty uniform swing between 2020 and 2024 across the US and across demographic types towards Trump and against the incumbent Democratic party. The swing was smaller in the US than in other countries that have held elections in 2024. And exit poll data, shown below, suggests inflation was to blame.

Those who said inflation caused them severe hardship were much more likely to vote for Trump. Some of the causality probably runs in reverse — people who vote for him were likely to say inflation caused them more severe hardship — but it is very hard to look at the results below and conclude that inflation was irrelevant.

Recommended newsletters for you

Free lunch — Your guide to the global economic policy debate. Sign up here

Trade Secrets — A must-read on the changing face of international trade and globalisation. Sign up here

#Fed #handle #Trump