The task for the next Archbishop of Canterbury is monumental

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is director of the religion and society think-tank Theos

The resignation of the 105th Archbishop of Canterbury this week showed an ancient institution coming face to face with a very 21st-century reckoning. The announcement of Justin Welby’s departure followed the Makin review into the Church of England’s failures in handling the abhorrent abuse inflicted by John Smyth.

In the end, Welby’s was a very modern resignation, complete with online petitions and people refreshing their phones for when the unprecedented news of the departure of the primate of the Anglican Communion would break. We saw how an institution that has moved in centuries tries to cope in a culture that deals in minutes.

The impact for the Church of England and indeed for Christianity as a whole — both in the UK but also within the Anglican Communion worldwide — cannot be overstated. Archbishops don’t resign; they are not CEOs. I imagine that Welby’s reluctance to quit was because of a deep sense that he was called by God to his position, despite the failures he admitted to.

In many ways, the Church of England is an institution ill at ease with itself. It is wrestling with the privilege and power that comes with being the established Church, whose boss — after God — is the King; all in an age when authority is not a given.

The past fortnight has seen more column inches dedicated to Church news than any time in recent memory. It is tragic that the story is the Church’s failing of the victims and survivors of abuse. The CofE has found itself on the wrong side, despite all its efforts in recent years to deal with cases of historic abuse and come up with plans to safeguard the most vulnerable.

But the story also shows that — despite the steep falls in attendance and ever-present anxiety over its future — people are still paying attention to the Church. It still matters when it fails.

The task now for the next Archbishop of Canterbury — “106” — will be a monumental one. Internally, to hold together a body of people with different beliefs about sexuality, racial justice, reparations, whether women should be priests. In this sense, it is like many other organisations — from the National Trust to the royal family — attempting to survive amid polarised views in a society that feels increasingly fragmented. Externally, he or she must work hard to regain trust.

The Church should play this clash of an ancient institution with a modern world to its advantage. Like the royal family, it needs to reinvent itself to become more approachable, although others will argue that conversely, it has moved too quickly and too wholeheartedly with the times.

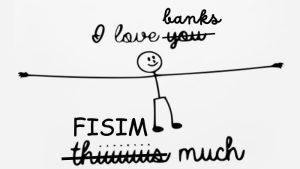

Unlike the royals, though, the product the Church is selling is not itself, but the gospel — a story that is about the ultimate divestment of power: God becoming a human. It’s about proximity rather than exclusivity, standing alongside the marginalised rather than covering up abuse. In a world of increasing turbulence and anxiety, what the Church is selling is being sought after in new and interesting ways. The fact that it has stood through the ups and downs of human history can itself provide comfort in a world of permacrisis.

For the Church of England to succeed, it will need to cut through the noise and shed itself of the perception that its ultimate priority is power. Walk into any local parish church — in rural settings, towns and cities up and down the country — and you will find tired, dedicated priests attempting to be a steady presence in their communities, while worrying about attendance figures and bake sales and food banks and how on earth to fix the leaky roof. Local churches’ contribution is not to be sniffed at. They are involved in 31,300 social action projects and run 14,100 of their own.

These feel far away from Church House in Westminster or Lambeth Palace. But the national and the local are two faces of the same body. As an institution, the Church of England occupies a unique role in the cultural landscape — attempting to provide the moral and national leadership that we need if we are to tackle our biggest challenges, whether climate change, AI or the ethics of assisted dying.

But neither the national institution nor the parish church can operate without trust. There had been signs that — amid general decline in trust in institutions — the Church was beginning to buck the trend. The World Values Survey at King’s College London found that confidence in churches and religious organisations in Britain fell from 49 per cent to 31 per cent between 1981 and 2018. Post-Covid, it had risen again to 42 per cent. In a cost of living crisis, churches provide a safety net; when riots set towns on fire and tragedies happen, churches hold space for collective grief. Trust remains at a local level, but there is no doubt that rebuilding it on a national one is a significant task. I pray that — for all our sakes — it succeeds.

#task #Archbishop #Canterbury #monumental