Far right gains traction in EU assembly on climate and top appointments

EU centre-right lawmakers are increasingly teaming up with the far right to dismantle the bloc’s green agenda, push for stricter curbs on immigration and set ultimatums on the formation of a new European Commission.

The new European parliament following elections in June has broken with decades of centrist consensus, highlighting deep political divides that are splitting a continent where hard right parties are now in government in five of the EU’s 27 member states.

“It’s a humiliation,” said one senior Socialist lawmaker about the largest political group, the centre-right European People’s party allying itself with the far right on several issues. “Trust is broken. The EPP has decided to create a new majority with the extreme right.”

Tensions between the Socialists, the second-largest group, and the EPP came to a head this month over Teresa Ribera, Spain’s pick for commissioner and a Socialist party champion.

Ribera currently serves as Spanish environment minister and has come under fire back home over the mismanagement of deadly floods last month.

The EPP refused to confirm her for the EU job until she appeared at a hearing in the Spanish parliament on Wednesday, in which she blamed the regional government of Valencia for having sent emergency alerts only after the first towns were already under water.

EU Socialists in turn withheld their votes on six other candidates, raising the prospect that Ursula von der Leyen’s new commission would not take office on December 1 as planned. The parties secured a compromise on Wednesday night.

After the June elections, the three centrist groups in the EU assembly — EPP, the Socialists, and liberal Renew — had agreed to form a “pro-European” majority which, backed by the Greens, would garner the votes for von der Leyen’s second term at the helm of the commission.

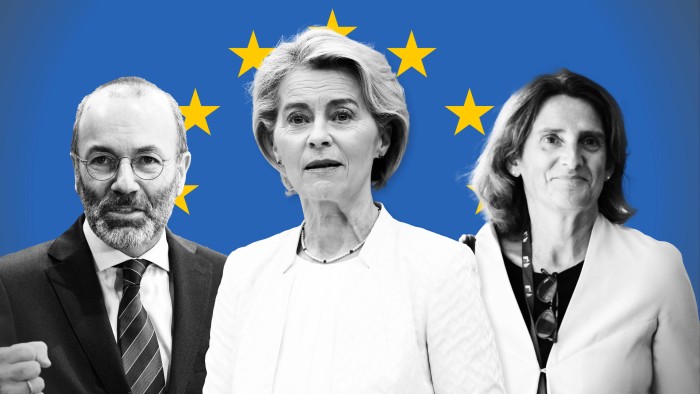

But Manfred Weber, the EPP parliamentary leader, has been accused by his partners of breaking that deal by teaming up with the far-right Patriots group led by the party of France’s Marine Le Pen and Hungary’s Viktor Orbán and with the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) where Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy are the biggest force.

Weber defended his actions and told the Financial Times Ribera had to be accountable to Spanish lawmakers. “The country is in shock. It’s fair to say, ‘clean your table and then you can ask for upgraded responsibility on a European level’.”

Weber previously pointed out that the Socialists started the spat by trying to downgrade Raffaele Fitto, a minister in Meloni’s government it put forward as its commissioner candidate. Von der Leyen had named him as one of six vice-presidents which the Socialists said was unacceptable because the ECR group was not part of the pro-EU alliance.

But as the fourth-largest group, the ECR has sufficient votes to safely get von der Leyen’s team over the line, given that the Greens and Renew lost seats compared to the previous term.

Terry Reintke, co-leader of the Greens, said that there was a “taste in the EPP to break this pro-European coalition” and they had an “appetite to fight” until the end of the mandate.

Over the past three months, the EPP has repeatedly voted with the Patriots and the ECR in internal meetings, a senior parliament official said.

The EPP’s desire to pick apart policies it had agreed to in the last term was on display on the EU’s budget, on foreign policy issues including Venezuela and on delaying the bloc’s tougher regime on importers of agricultural products, which led to forests being felled.

On the deforestation law, the EPP secured its request for some European farmers to be exempt with the help of the far-right Alternative for Germany, also a member of Le Pen’s Patriots group. But EU ambassadors who have the last say on the bill on Wednesday scrapped that exemption, while approving the delay.

The Patriots, who are the third-largest group, said these victories proved they are “a decisive force in the European parliament” and aimed to “solidify this alternative majority”.

Reintke said that Weber wanted “to be able to dismantle” the bloc’s Green Deal aimed at decarbonising Europe’s economy. “If EPP is going to open one file after another how do we prevent that happening? They always have a far-right majority.”

Some EPP figures back his approach. “The Socialists have woken up in a new parliament and they have to adjust,” said one. “We had to swallow things in the last five years we didn’t like. Elections have consequences.”

“Not everything will pass with the majority of the past,” said Christian Ehler, a German EPP member.

The rightwing alliance in Brussels does not always translate well in national capitals. In Poland, Prime Minister Donald Tusk’s Civic Platform party, which is part of the EPP, is in a fierce battle with the ECR’s Law and Justice (PiS) party led by his political arch-rival, Jaroslaw Kaczynski, ahead of presidential elections next year.

In Hungary, EPP member Tisza is trying to defeat Orban. By contrast, in the Netherlands, Sweden and Finland the EPP governs together with ultraconservative or far-right parties.

“Clearly Weber thinks he can use the Patriots to get his line through but if you sup with the devil beware,” the senior EP official said. “It’s a completely new world and the Socialists and Liberals don’t know how to deal with it.”

Nicolai von Ondarza, of the German Institute for International & Security Affairs, said that the EPP’s normalisation of the ECR could cause problems beyond the parliament. “It will be much more difficult and contentious for von der Leyen,” he said, while making it hard to pass legislation.

“You cannot govern the EU without a stable majority,” said a senior EU official.

Data visualisation by Steven Bernard

#gains #traction #assembly #climate #top #appointments