Shrinking vision of Skills England casts doubt on big fixes needed

This article is an on-site version of our The State of Britain newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every week. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

Good afternoon. Labour made much of its “growth mission” in its election manifesto — an ambitious mix of regulatory and planning reforms built around an industrial strategy designed to strategically back eight key growth sectors.

At the heart of this project lies a significant tension between a centralising strategic grip and renewed impetus for devolution — to wit, Local Growth Plans, a New Towns task force and the further streamlining of district councils, for which a white paper is expected next week.

In theory, government wants the national and local visions to intersect: local clusters where the UK has comparative economic advantage supported by centrally enabled but locally delivered skills support, infrastructure and public and private investment.

In practice, there are some early warning lights now blinking about Labour’s ability to turn this high-level manifesto commitment into concrete reality.

Take the skills agenda. Labour’s election manifesto promised to create a new overarching body, Skills England, to get the tangled web of universities, further education colleges and business pulling together to deliver more skills to support growth sectors.

Launching the project in July within weeks of winning power, Labour made a big deal of this plan. Sir Keir Starmer said the skills system was “in a mess” and that the new body would “transform” the skills landscape, kick-start growth and reduce the need for imported skills.

The prime minister returned to the subject in his party conference speech in October to announce new foundation apprenticeships and a promise to “get our skills system right”. The impression was given that Skills England was going to be a key pillar of Labour’s transformation agenda.

And yet, and yet. It has now emerged that Skills England is not going to be an independent body, with powers to bestride Whitehall departments and drive (sorely lacking) business investment in skills.

Instead, it is going to be an “executive agency” within the Department for Education (DfE) with a boss appointed at the relatively lowly level of director in the civil service, with no statutory powers to consult employers.

As one business leader put it: “How is a director-level civil servant going to be able to pick up the phone to anyone that matters?”

The yawning gap between the rhetoric and reality has caused a cross-party consternation. Education, industry and business groups all warned this week that things appear to be heading in the wrong direction.

But set aside for one second whether Skills England was a good idea in the first place.

The more urgent question that arises is why the government first bigged up Skills England and then reduced it to what one official witheringly called “a glass box in the DfE”. What does that say about the internal guts of the government?

There was real interest in the potential of this body. I am told 800 of the great and the good of the skills and education world have applied to be on the board of Skills England. I wonder how many are interested now?

What does it say about the strategic coherence of a government, and the level of actual planning and thinking that went into its manifesto, that it should send out such conflicting and confusing signals about its intentions?

The bleak answer to that question is that there wasn’t much real thinking, or indeed actual ambition. As another Whitehall insider put it, announcing a quango with no meat behind it inside the first 100 days should have been an early red flag.

The more charitable answer is that ministers are working things out as they go along, and we have to wait for the spending review and the outcome of the industrial strategy consultation before all these policies properly coalesce. Neither is very comforting.

Confused messaging aside, there is still considerable debate about exactly how a body like Skills England should look to narrow skills gaps in areas that are key to the government’s ambitions — on say, housebuilding, the green transition or life sciences.

Because as this Learning & Work Institute paper notes, over the decades there have been a multitude of bodies trying to “fix” the UK’s skills gaps with limited success.

There was the Manpower Services Commission, Training and Enterprise Councils, Sector Skills Development Agency, Learning and Skills Council, UK Commission for Employment and Skills, and the Institute for Apprenticeships and Technical Education (IfATE) — which Skills England will supersede.

What makes anyone think it will be different this time?

Optimists such as Professor Andy Westwood at the Productivity Institute argue (paper here) that there is a case for creating a “strategic brain” for a better UK skills system, to “influence the needs and behaviours of employers and individuals — in choices, investment and the utilisation of any skills.”

But as he notes: “it can’t just be the brain — it will need to have some brawn too.” That means having levers over “funding, regulation and strategic interventions” to enable it to yoke together policy across multiple Whitehall departments including business, net zero, housing — and, of course, Treasury. A piddly thing in DfE is not that.

Because as the Learning & Work Institute argues, to be effective, Skills England has to get the “true buy-in” of a range of different actors. This has been key to the success of bodies like the Low Pay Commission or Monetary Policy Committee:

It also needs to be truly independent and carry weight, owned by national and local government and by employers and trade unions, rather than being solely a Department for Education body with a board of stakeholder representatives.

Still, it is easy to overstate the importance of architecture. The reality is that the £2.5bn or so raised by the Apprenticeship Levy (now the Growth and Skills Levy) is a tiny fraction of the £50bn-plus spent by companies in training staff every year.

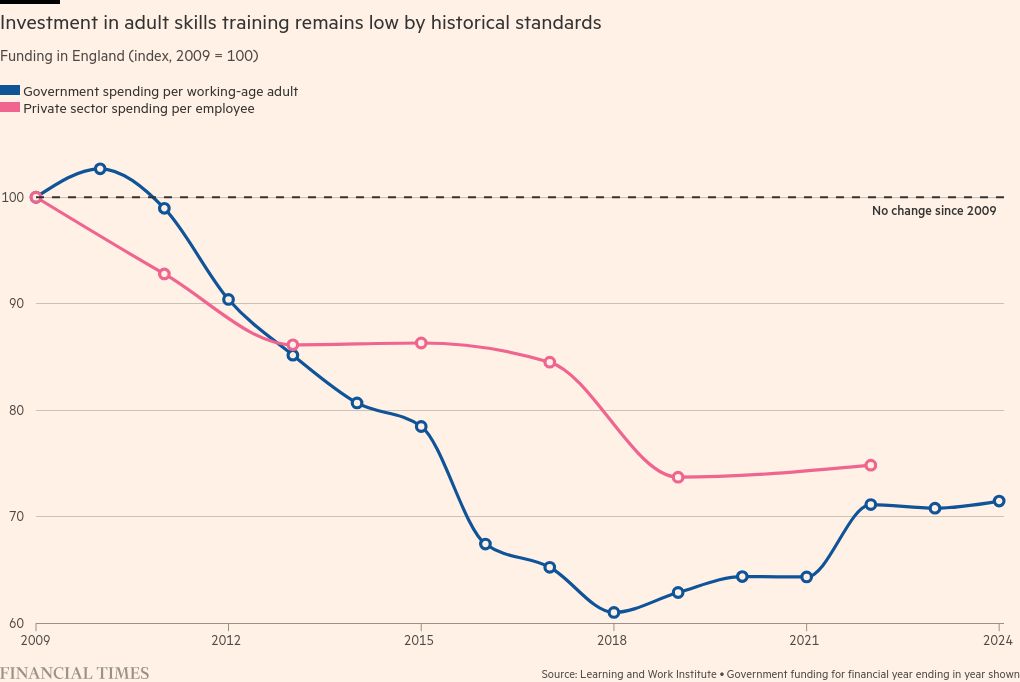

That investment has been falling, however, over the last 20 years. Employers are investing 26 per cent less in training per employee than in 2005, according to LWI calculations, with graduates getting a bigger slice of the (shrinking) training pie than non-graduates.

The decision to de-fund Level 7 (masters degree equivalent) apprenticeships is a nod to this, but fundamentally change must be driven by demand in business. It will not come from an under-resourced FE system that pays its staff £9,000 less than the average secondary school teacher.

As Graham Hasting-Evans, the chief executive of skills charity NOCN Group puts it, the transformation must come from within the existing workforce, not just the new entrants who only account for about 2 per cent of workers each year.

“I’ve got nothing against improving skills in FE colleges, but we won’t change the economy if we rely on that. We’ve got to get employers to improve the quality of the rest of the workforce,” he says.

In summary, there is a case for better overall direction, as Westwood and others maintain, even if this should not be overstated. But siloing Skills England inside the DfE sends out a very conflicted signal to the market.

Don’t miss the latest incisive briefings by longtime trade specialist Alan Beattie, whose Trade Secrets guides you through the biggest stories in international trade and globalisation. Sign up to the weekly newsletter here.

Britain in numbers

This week’s chart will send further chills around the DfE. It shows the number of childminders in England continues to fall, just as the government ramps up its offering of funded childcare to parents, writes Laura Hughes.

The latest data shows there were more than 1,000 fewer childminders registered with Ofsted this year when compared to last. At the end of August, there were 26,000 childminders, down from 27,060.

Unlike nurseries, childminders are able to offer home-based care to smaller groups of children and often more flexible hours for parents than traditional nurseries. The data on falling childminders is another reminder that the sector, with its chronic low rates of pay and high staff turnover, may struggle to actually provide places for these children.

Labour ministers are continuing to roll out the last government’s £4bn flagship policy to provide parents of children from nine months to school age in England with 30 hours of free childcare a week, by next September.

The decline in childminders is partly a reflection of the financial strain faced by all childcare providers, with the government funding for these “free” hours historically lower than the actual cost of providing the care.

Neil Leitch, chief executive of the Early Years Alliance, an educational charity and membership group, said that support to tackle the drop-off in childminder numbers had never been more important.

“This means implementing policies which support childminders to both join and remain in the sector and funding — for the entirety of the early years sector — which reflects the true cost of delivering early education and care. After all, as these figures show, time is fast running out.”

The State of Britain is edited by Georgina Quach today. Premium subscribers can sign up here to have it delivered straight to their inbox every Thursday afternoon. Or you can take out a Premium subscription here. Read earlier editions of the newsletter here.

Recommended newsletters for you

Inside Politics — What you need to know in UK politics. Sign up here

Europe Express — Your essential guide to what matters in Europe today. Sign up here

#Shrinking #vision #Skills #England #casts #doubt #big #fixes #needed