Eurozone wages rise by 5.4% in third quarter

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

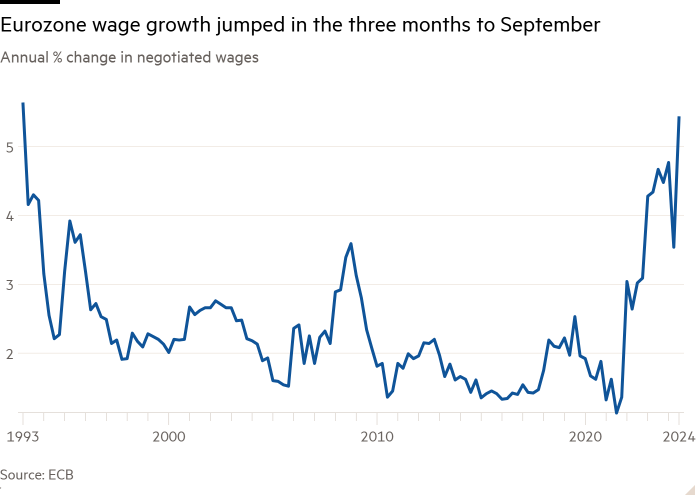

Eurozone wages have risen at their fastest rate since the 1990s, according to data published by the European Central Bank that could complicate policymakers’ plans for more interest rate cuts.

Negotiated wages jumped 5.4 per cent in the three months to September compared with the year-ago period, up from an annual rise of 3.5 per cent in the previous quarter, the European Central Bank said on Wednesday. It was the biggest increase since 1993, six years before the euro was launched.

Growth in wage deals is closely watched by monetary policymakers as a signal of persistent inflationary pressures. The ECB had expected a pick-up in negotiated wage growth during the second half of this year, mostly due to one-off agreements in Germany, the EU’s largest economy.

However, it forecasts a sharp decline in negotiated wage growth, which excludes bonuses, overtime and other forms of compensation, in the second half of 2025, to a rate consistent with its 2 per cent medium-term inflation target, as price pressures abate and the labour market weakens.

As a result the ECB was likely to “look through” the strong wage data, said Andrzej Szczepaniak, economist at the financial company Nomura. He pointed to survey data showing a weakening of companies’ pricing power in the fourth quarter, “which will result in consumer inflationary pressures abating further over the coming months”.

The ECB has lowered interest rates three times this year, taking borrowing costs to 3.25 per cent, and is widely expected to make another quarter-point cut at its next meeting on December 12 amid signs of softening inflation and stagnant demand.

Elias Hilmer, economist at Capital Economics, said wage growth was a lagging indicator of inflationary pressures as it includes all agreements that are currently in place regardless of when they were signed, “meaning that it doesn’t pick up turning points as quickly as indicators for newly agreed wages only”.

More timely indicators, such as a tracker of salaries for vacancies compiled by recruitment portal Indeed with the Central Bank of Ireland, have been on a downward trend since mid-2022.

IG Metall, Germany’s largest industrial union, recently struck a deal securing a 5.5 per cent pay rise over 25 months, much lower than the 8.5 per cent increase in the previous round.

ECB chief economist Philip Lane said in the summer that he expected wage growth to slow sharply in 2025 and 2026 as “the catch-up” in salaries was “peaking”

Annual inflation in the Eurozone rose to 2 per cent in October, from 1.7 per cent in the previous month. However, concerns over flat economic growth have become more pressing than those about inflation. Germany is facing its first two-year recession since the early 2000s.

Earlier in the week the European Commission downgraded its growth forecasts for the Eurozone, warning the 20-country bloc is set to fall further behind the US.

At 6.3 per cent, unemployment in the Eurozone is still at a record low rate, but job vacancies are falling and fewer businesses report labour shortages, indicating the labour market is becoming less tight.

“A loosening of the Eurozone’s labour market and lower inflation mean that workers are likely to push for smaller nominal wage rises in 2025,” said Hilmer.

“While at face value the data released look concerning, the bigger picture is that wage growth is likely to slow significantly next year,” he added.

#Eurozone #wages #rise #quarter