Is France heading for a Greek-style debt crisis?

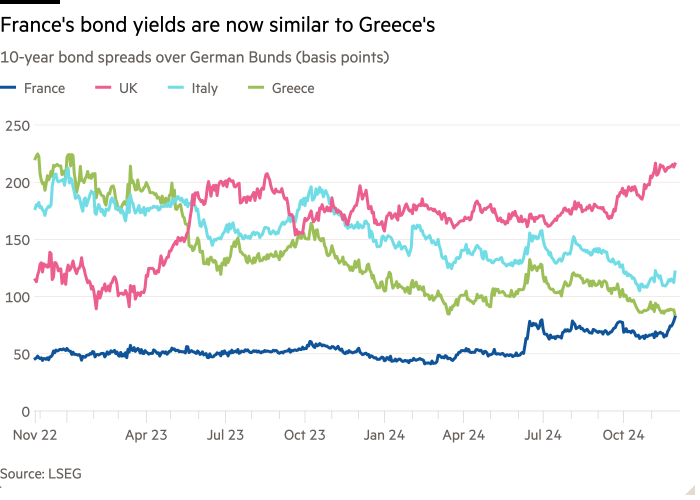

France’s borrowing costs have surpassed those of Greece as investors fret about the French government’s ability to pass a deficit-trimming budget — and its ability to survive at all.

The far-right Rassemblement National, led by Marine Le Pen, has threatened to back a censure motion against the government as soon as next week unless its demand for changes to the 2025 finance bill are met.

Prime minister Michel Barnier responded by dramatising the situation in the hope that his opponents will back down or risk being blamed for market chaos. He earlier this week warned of “a big storm” on financial markets if his minority government was toppled.

Government spokesperson Maud Bregeon said France was facing a possible “Greek scenario”. Finance minister Antoine Armand likened France to “high-flying airliner at risk of stalling”.

Is France really facing a Greek style debt crisis?

“For the moment, it is a complete exaggeration,” said Éric Heyer, an economics professor at Sciences Po.

France has full access to debt markets. It raised €8.3bn on Monday. The 10-year yield on French government debt stands at some 3 per cent. At the height of its debt crisis, the yield on Greek debt climbed above 16 per cent. The Greek economy had cratered, made worse by punishing austerity measures, and Athens engaged in a bitter fight with Berlin and Brussels over the terms of a Eurozone bailout.

During France’s recent political turmoil, the spread between its debt and German debt has widened by a mere 0.3 percentage points, Heyer said.

Nonetheless, investors are rattled by the combination of political paralysis and parlous public finances. The public deficit is likely to hit 6.2 per cent of GDP and Paris is under pressure from the markets and the EU to take corrective action.

Although France has not run a balanced budget for five decades, it has reached a point where it can no longer rely on economic growth to keep debt sustainable, the country’s Council of Economic Analysis noted earlier this year.

Why is passing the budget proving so difficult?

For two reasons, said Antoine Bristielle, director of the opinion observatory at the Fondation Jean Jaurès think-tank.

First, the government has no absolute majority, meaning any text requires negotiation with RN or the leftwing Nouveau Front Populaire bloc. Second, the tight public finances mean Barnier is making difficult and unpopular choices to meet his target of bringing the deficit down from 6 per cent to 5 per cent of GDP in 2024.

He has proposed a €60bn consolidation package, which he claimed would be mostly spending cuts but actually relies heavily on tax increases. It is unacceptable to the RN and the NFP, which both campaigned this summer on promises to increase the purchasing power of French people.

There has also been resistance from President Emmanuel Macron’s centrist alliance and the centre-right Republicans who nominally support Barnier’s government.

With little room for manoeuvre, Barnier has said it is likely he will be forced to use a constitutional procedure known as a 49.3, which enables the government to pass legislation without a parliamentary vote but also exposes it to a motion of no confidence.

The left-wing bloc has promised to file such a motion and now the RN could give it the votes needed to succeed.

This could happen as soon as next week, when parliament votes on a social security financing bill, an adjunct to the budget, or later in the month. The budget must be passed by December 21.

What is Le Pen’s game?

The far-right leader has demanded Barnier abandon higher electricity levies and come up with bigger spending cuts instead. She also wants to keep the indexation of pensions to inflation, reimbursement of medication costs and employer social security tax breaks. Last week, she threatened to bring down the government if she did not get her way.

Barnier sought to pressure her by implicitly saying she would be to blame for the financial turmoil that would ensue if the budget failed and the government fell. The RN has retorted that there will be no financial chaos or US-style government shutdown, because the 2024 budget could be rolled over with special legislation.

Bristielle said: “[The RN’s] problem is that they have both a strategy of being considered as a respectable party that . . . guarantees some stability, while also not disappointing their electorate.”

Barnier on Thursday blinked first, abandoning the planned increase in electricity taxes albeit at a cost of €3.8bn.

It is a major concession to the RN. But some analysts say Le Pen may have decided her tacit support for Barnier’s increasingly unpopular government is no longer worth the political costs. One factor may be the judgment due next March in her trial for embezzling EU funds, for which she could be barred from holding public office, ending her presidential ambitions.

“Why should she appear stateswomanlike when she risks not being able to run for the presidency in three years’ time?” Mujtaba Rahman, managing director of Eurasia Group wrote in a note to clients, pointing to Le Pen’s switch from conciliatory to populist rhetoric in recent days.

Is France becoming ungovernable?

The difficulties in passing the budget do not bode well for the long-term survival of Barnier’s government or the future governability of France.

If the government were to fall, parliament could pass emergency legislation to rollover this year’s budget.

If Macron were somehow able to appoint a new government, it could seek to renegotiate the budget, with less ambitious cost-saving measures, Heyer said. However, the possibilities of forming any parliamentary majority are only narrowing.

There is also the possibility of a “technical government” being put in place, with limited decision-making power, until new legislative elections can be held in the summer, a year after France last voted, which is the earliest possible under the constitution.

Ultimately, prolonged paralysis is likely to heap pressure on Macron to resign to allow for a political reboot through a fresh presidential election.

Bristielle said: “I’m not sure that leaving power is at the centre of his strategy. Nevertheless, he has shown that he can surprise us, to say the least.”

Data visualisation by Keith Fray

#France #heading #Greekstyle #debt #crisis